Orkney

| Orkney United Kingdom | |

| File:Mainland orkney robben.jpg | |

|---|---|

| Flag of Orkney | |

| Flag | |

| Boreas Domus Mare Amicus (Home to the winds, friend of the sea) | |

| Orkney | |

| [Interactive map] | |

| Area: | 376 square miles |

| Population: | 21,349 |

| County town: | Kirkwall |

| County flower: | Bearberry [2] |

Orkney is a shire consisting of a group of islands lying 10 miles north of the coast of Caithness. Orkney has approximately 70 islands of which 20 are inhabited.[1][2]

The largest island, known as the Mainland and has an area of 202 square miles making it the tenth-largest island in the British Isles. The largest town and the islands’ capital is Kirkwall on Mainland.[3]

In addition to the Mainland, most of the islands are in two groups, the North and South Isles, all of which have an underlying geological base of Old Red Sandstone. The climate is mild and the soils are extremely fertile, most of the land being farmed. Agriculture is the most important sector of the economy and the significant wind and marine energy resources are of growing importance. The local people are known as Orcadians and have a distinctive dialect and a rich inheritance of folklore. There is an abundance of marine and avian wildlife.

Orkney contains some of the oldest and best-preserved Neolithic sites in Europe, and the "Heart of Neolithic Orkney" is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site. As the isles are largely treeless, building in all ages has been done in stone, which has left in the landscape across the islands a remarkable record of past ages. The islands have been inhabited for at least 8,500 years, as Mesolithic and Neolithic folk have left their mark. In the Iron Age the islands are assumed to have been occupied by Picts, whose enigmatic carvings and strong brochs are found on many islands.

In the ninth century or earlier, Orkney colonised by the Norse; no trace of the previous inhabitants remains in the language, place-names nor culture of Orkney except in the name of Orkney itself and so it is assumed to have been an uncompromising takeover. The islands were annexed by Norway in 875 and ruled by Earls. The islands passed to the Scottish Crown in 1468 as a pledge for a dowry settlement which was never redeemed and the islands were annexed in 1472. They had gradually been settled by Scots for some ages before.

Name of the county

The name "Orkney" is Norse in form but has a much earlier origin; the islands were known as the Orcades at least by the 1st century AD,

Pytheas of Massilia visited Britain at some time between 322 and 285 BC and described it as being triangular in shape, with a northern tip called Orcas.[4] This may have referred to Dunnet Head, from which Orkney is visible.[5] Writing in the 1st century AD, the Roman geographer Pomponius Mela called the islands Orcades, as did Tacitus in AD 98, claiming that his father-in-law Agricola had "discovered and subjugated the Orcades hitherto unknown"[5][6] although both Mela and Pliny the Elder had previously referred to the islands.[4] "Orc" is usually interpreted as a Pictish tribal name meaning "young pig" or "young boar".[7]

The old Irish Gaelic name for the islands was Insi Orc (which may be translated "island of the pigs").[8][9][Notes 1]

When Norwegian Vikings arrived on the islands they assimilated the orc to their own orkn which is Old Norse for seal and added the suffix ey meaning "island".[11] Thus the name became Orkneyjar (meaning "seal islands")[9] which was rendered Orcanege in English.[12]

History

Prehistory

A charred hazelnut shell, recovered in 2007 during excavations in Tankerness on the Mainland has been dated to 6820-6660 BC indicating the presence of Mesolithic nomadic tribes.[13]

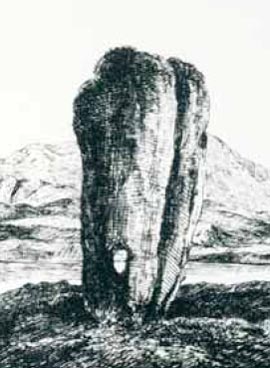

The earliest known permanent settlement is at Knap of Howar, a Neolithic farmstead on the island of Papa Westray, which dates from 3500 BC. The village of Skara Brae, Europe's best-preserved Neolithic settlement, is believed to have been inhabited from around 3100 BC.[14] Other remains from that era include the Standing Stones of Stenness, the Maeshowe passage grave, the Ring of Brodgar and other standing stones. Many of the Neolithic settlements were abandoned around 2500 BC, possibly due to changes in the climate.[15][16][17]

During the Bronze Age fewer large stone structures were built although the great ceremonial circles continued in use[18] as metalworking was slowly introduced to Scotland from Europe over a lengthy period.[19][20] There are relatively few Orcadian sites dating from this era although there is the impressive Plumcake Mound near the Ring of Brodgar and various islands sites such as Tofts Ness on Sanday, Orkney|Sanday and the remains of two houses on Holm of Faray.[21][22]

Iron Age

Excavations at Quanterness on the Mainland have revealed an Atlantic roundhouse built about 700 BC and similar finds have been made at Bu on the Mainland and Pierowall Quarry on Westray.[23] The most impressive Iron Age structures of Orkney are the ruins of later round towers called "brochs" and their associated settlements such as the Broch of Burroughston[24] and Broch of Gurness. The nature and origin of these buildings is a subject of ongoing debate. Other structures from this period include underground storehouses, and aisled roundhouses, the latter usually in association with earlier broch sites.[25][26]

During the Roman invasion of Britain the "King of Orkney" was one of 11 British leaders who is said to have submitted to the Emperor Claudius in AD 43 at Camulodunum.[27][Notes 2] After the Agricolan fleet had come and gone, possibly anchoring at Shapinsay, direct Roman influence seems to have been limited to trade rather than conquest.[30]

By the late Iron Age, it is believed that Orkney was part of the Pictish kingdom, and although the archaeological remains from this period are less impressive there is every reason to suppose the fertile soils and rich seas of Orkney provided a comfortable living.[30][Notes 3] The Gaels began to influence the islands towards the close of the Pictish era, perhaps principally through the role of missionaries, as evidenced by several islands bearing the epithet "Papa" in commemoration of these preachers.[32] However, before the Gaelic presence could establish itself the Picts were gradually dispossessed by the Norsemen from the late 8th century onwards. The nature of this transition is controversial, and theories range from peaceful integration to enslavement and genocide.[33]

The Norse in Orkney

Both Orkney and Shetland saw a significant influx of Norwegian settlers during the late 8th and early 9th centuries. Vikings made the islands the headquarters of their pirate expeditions carried out against Norway and the coasts of mainland Scotland. In response, Norwegian king Harald Hårfagre ("Harald Fair Hair") annexed the Northern Isles (comprising Orkney and Shetland) in 875. Rognvald Eysteinsson received from Harald and the title ‘’Jarl’’ (or “Earl”) and with it rule over Orkney and Shetland, as reparation for the death of his son in battle in Scotland. Rognvald then passed the earldom on to his brother Sigurd the Mighty.[34]

However, Sigurd's line barely survived him and it was Torf-Einarr, Rognvald's son by a slave, who founded a dynasty which retained control of the islands for centuries after his death.[35][Notes 4] He was succeeded by his son Thorfinn Skull-splitter and during this time the deposed Norwegian King Eric Bloodaxe often used Orkney as a raiding base before being killed in 954. Thorfinn's death and presumed burial at the broch of Hoxa, on South Ronaldsay, led to a long period of dynastic strife.[37][38]

The islands were Christianised by Olav Tryggvasson, King of Norway in 995 when he stopped at South Walls on his way from Ireland to Norway. The King summoned the earl Sigurd the Stout[Notes 5] and said "I order you and all your subjects to be baptised. If you refuse, I'll have you killed on the spot and I swear I will ravage every island with fire and steel." Unsurprisingly, Sigurd agreed and the islands became Christian at a stroke,[39] receiving their own bishop in the early 11th century.[Notes 6]

Thorfinn Sigurdsson (“Thorfinn the Mighty”) was a son of Sigurd and a grandson of King Malcolm II of Scotland. Along with Sigurd's other sons he ruled Orkney during the first half of the 11th century and extended his authority over a small maritime empire stretching from Dublin to Shetland. Thorfinn died around 1065 and his sons Paul and Erlend succeeded him, fighting at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066.[42] Paul and Erlend quarreled as adults and this dispute carried on to the next generation. The "martyrdom" of Magnus Erlendsson, who was killed in April 1116 by his cousin Haakon Paulsson, resulted in the building of St Magnus Cathedral, still today a dominating feature of Kirkwall.[Notes 7][Notes 8]

Unusually, from c. 1100 onwards the Norse earls owed allegiance both to Norway for Orkney and to the Scottish crown through their holdings as Earls of Caithness.[45] In 1231 the line of Norse earls, unbroken since Rognvald, ended with Jon Haraldsson's murder in Thurso.[46] The Earldom of Caithness was granted to Magnus, second son of the Earl of Angus, whom Haakon IV of Norway confirmed as Earl of Orkney in 1236.[47] In 1290 the death of the child princess Margaret, Maid of Norway in Orkney on the way to Scotland created a disputed succession which led to the Wars of Scottish Independence.[48][Notes 9]

In 1379 the earldom passed to the Sinclair family, who were also barons of Roslin near Edinburgh.[49]

Evidence of the Viking presence is widespread, and includes the settlement at the Brough of Birsay,[50] the vast majority of place names,[51] and the twelfth century runic inscriptions carved into the stones in the interior of Maeshowe.

Scottish rule

In 1468 Orkney was pledged by Christian I of Denmark, in his capacity as king of Norway, as security against the payment of the dowry of his daughter Margaret, betrothed to James III of Scotland. As the money was never paid, the connection with the crown of Scotland has become perpetual.[Notes 10]

The history of Orkney prior to this time is largely the history of the ruling aristocracy. From now on the ordinary people emerge with greater clarity. An influx of Scottish entrepreneurs helped to create a diverse and independent community that included farmers, fishermen and merchants that called themselves comunitatis Orcadie and who proved themselves increasing able to defend their rights against their feudal overlords.[54][55]

From at least the 16th century, boats from mainland Scotland and the Netherlands dominated the local herring fishery. There is little evidence of an Orcadian fleet until the 19th century but it grew rapidly and 700 boats were involved by the 1840s with Stronsay and then later Stromness becoming leading centres of development. White fish never became as dominant as in other Scottish ports.[56]

A British county

Scotland and England were brought together under one crown in 1603, and united in 1707, bringing Orkney within the one Kingdom of Great Britain and opening new opportunities for Orcadians. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Orcadians formed the overwhelming majority of employees of the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada. The harsh climate of Orkney and the Orcadian reputation for sobriety and their boat handling skills made them ideal candidates for the rigours of the Canadian north.[57] During this period, burning kelp briefly became a mainstay of the islands' economy. For example, on Shapinsay over 3,000 tons of burned seaweed were produced each year to make soda ash, bringing in £20,000 to the local economy.[58]

Agricultural improvements beginning in the 18th century resulted in the enclosure of the commons and ultimately in the 19th century came the emergence of large and well-managed farms using a five-shift rotation system and producing high quality beef cattle.[59]

20th century

Orkney was the site of a Royal Navy base at Scapa Flow, which played a major role in both First World War and Second World War. After the Armistice in 1918, the German High Seas Fleet was transferred in its entirety to Scapa Flow while a decision was to be made on its future; however, the German sailors opened their sea-cocks and scuttled all the ships. Most ships were salvaged, but the remaining wrecks are now a favoured haunt of recreational divers.

One month into Second World War, the Royal Navy battleship HMS Royal Oak was sunk by a German U-boat in Scapa Flow. As a result, barriers were built to close most of the access channels; these had the additional advantage of creating causeways enabling travellers to go from island to island by road instead of being obliged to rely on ferries. The causeways were constructed by Italian prisoners of war, who also constructed the ornate Italian Chapel on Lamb Holm.[60]

The navy base was run down after the war, eventually closing in 1957. The problem of a declining population was significant in the post-war years, although in the last decades of the 20th century there was a recovery and life in Orkney focused on growing prosperity and the emergence of a relatively classless society.[61]

Geography

The Pentland Firth, the a seaway which separates Orkney from the mainland of Great Britain is 6 miles wide between Brough Ness on the island of South Ronaldsay and Duncansby Head in Caithness. Orkney lies between 58°41′and 59°24′North, and 2°22′and 3°26′West, measuring 50 miles from northeast to southwest and 29 miles from east to west, and covers 376 square miles.[62]

The islands are mainly low-lying except for some sharply rising sandstone hills on Hoy, Mainland and Rousay and rugged cliffs on some western coasts. Nearly all of the islands have lochs, but the watercourses are merely streams draining the high land. The coastlines are indented, and the islands themselves are divided from each other by straits generally called "sounds" or "firths".[63]

The tidal currents, or "roosts" as some of them are called locally,[64] off many of the isles are swift, with frequent whirlpools.[Notes 11] The islands are notable for the absence of trees, which is partly accounted for by the amount of wind.[66]

Islands

Orkney has 20 inhabited islands, and some 70 islands overall, with countless islets, rocks and skerries. In island names, the suffix "a" or "ay" represents the Norse ey, meaning "island". Those described as "holms" are very small.

Mainland

- Main article: Mainland, Orkney

The Mainland is the largest island of Orkney. Both of Orkney's burghs, Kirkwall and Stromness, are on this island, which is also the heart of Orkney's transportation system, with ferry and air connections to the other islands and to the outside world. The island is more densely populated (75% of Orkney's population) than the other islands and has much fertile farmland.

The island is mostly low-lying (especially East Mainland) but with coastal cliffs to the north and west and two sizeable lochs: the Loch of Harray and the Loch of Stenness. The Mainland contains the remnants of numerous Neolithic, Pictish and Norse constructions. Four of the main Neolithic sites are included in the “Heart of Neolithic Orkney World Heritage Site”, defined in 1999.

The other islands in the group are classified as north or south of the Mainland. Exceptions are the remote islets of Sule Skerry and Sule Stack, which lie 40 miles west of the archipelago, but form part of the county

The North Isles

The northern group of islands is the most extensive and consists of a large number of moderately sized islands, linked to the Mainland by ferries and by air services. Farming, fishing and tourism are the main sources of income for most of the islands.

The most northerly is North Ronaldsay, which lies 2½ miles beyond its nearest neighbour, Sanday. To the west is Westray has a population of 550. It is connected by ferry and air to Papa Westray, also known as "Papay". Eday is at the centre of the North Isles. The centre of the island is moorland and the island's main industries have been peat extraction and limestone quarrying.

Rousay, Egilsay and Gairsay lie north of the west Mainland across the Eynhallow Sound. Rousay is well known for its ancient monuments, including the Quoyness chambered cairn and Egilsay has the ruins of the only round-towered church in Orkney. Wyre to the south east contains the site of Cubbie Roo's castle. Stronsay and Papa Stronsay lie much further to the east across the Stronsay Firth. Auskerry is south of Stronsay and has a population of only five. Shapinsay and its Balfour Castle are a short distance north of Kirkwall.

Other small uninhabited islands in the North Isles group include: Calf of Eday, Damsay, Eynhallow, Faray, Helliar Holm, Holm of Faray, Holm of Huip, Holm of Papa, Holm of Scockness, Kili Holm, Linga Holm, Muckle Green Holm, Rusk Holm and Sweyn Holm.

The South Isles

The southern group of islands surrounds Scapa Flow. Hoy is the second largest of the Orkney Isles and Ward Hill at its northern end is the highest elevation in the archipelago. The Old Man of Hoy is a well-known seastack. Burray lies to the east of Scapa Flow and is linked by causeway to South Ronaldsay, which hosts the cultural events, the Festival of the Horse and the Boys' Ploughing Match.[67] It is also the location of the Neolithic Tomb of the Eagles.

Graemsay and Flotta are both linked by ferry to the Mainland and Hoy, and the latter is known for its large oil terminal. South Walls has a 19th-century Martello tower and is connected to Hoy by the Ayre. South Ronaldsay, Burray, Glims Holm, and Lamb Holm are connected by road to the Mainland by the Churchill Barriers.

Uninhabited South Islands include: Calf of Flotta, Cava, Copinsay, Corn Holm, Fara, Glims Holm, Hunda, Lamb Holm, Rysa Little, Switha and Swona. The Pentland Skerries lie further south, closer to mainland Caithness.

Parishes

Geology

The superficial rock of Orkney is almost entirely Old Red Sandstone, mostly of Middle Devonian age.[68] As in the neighbouring county of Caithness on Great Britain, this sandstone rests upon the metamorphic rocks of the Moine series, as may be seen on the Mainland, where a narrow strip is exposed between Stromness and Inganess, and again in the small island of Graemsay; they are represented by grey gneiss and granite.[69]

The Middle Devonian is divided into three main groups. The lower part of the sequence, mostly Eifelian in age, is dominated by lacustrine beds of the lower and upper Stromness Flagstones.[70] The later Rousay flagstone formation is found throughout much of the North and South Isles and East Mainland.[71]

The Old Man of Hoy is formed from sandstone of the uppermost Eday group that is up to 800 yards thick in places. It lies unconformably upon steeply inclined flagstones, the interpretation of which is a matter of continuing debate.[71][72]

The Devonian and older rocks of Orkney are cut by a series of WSW-ENE to N-S trending faults, many of which were active during deposition of the Devonian sequences.[73] A strong synclinal fold traverses Eday and Shapinsay, the axis trending north-south.

Middle Devonian basaltic volcanic rocks are found on western Hoy, on Deerness in eastern Mainland and on Shapinsay. Correlation between the Hoy volcanics and the other two exposures has been proposed, but differences in chemistry means this remains uncertain.[74] Lamprophyre Dike (geology)|dykes of Late Permian age are found throughout Orkney.[75]

Glacial striation and the presence of chalk and flint erratics that originated from the bed of the North Sea demonstrate the influence of ice action on the geomorphology of the islands. Boulder clay is also abundant and moraines cover substantial areas.[76]

Climate

Orkney has a cool temperate climate that is remarkably mild and steady for such a northerly latitude, due to the influence of the Gulf Stream.[77] The average temperature for the year is 8 °C (46 °F); for winter 4 °C (39 °F) and for summer 12 °C (54 °F).[78]

Winds are a key feature of the climate and even in summer there are almost constant breezes. In winter, there are frequent strong winds, with an average of 52 hours of gales being recorded annually.[79]

To tourists, one of the fascinations of the islands is their "nightless" summers. On the longest day, the sun rises at 03:00 and sets at 21:29 GMT and complete darkness is unknown. This long twilight is known in the Northern Isles as the "simmer dim".[80] Winter nights are long. On the shortest day the sun rises at 09:05 and sets at 15:16.[81] At this time of year the aurora borealis can occasionally be seen on the northern horizon during moderate auroral activity.[82]

Natural history

Orkney has an abundance of wildlife especially of grey and common seals and seabirds such as puffins, kittiwakes, tysties (guillimots), ravens, and bonxies (great skuas). Whales, dolphins, otters are also seen around the coasts.

Inland the Orkney vole, a distinct subspecies of the common vole is an endemic.[83][84] There are five distinct varieties, found on the islands of Sanday, Westray, Rousay, South Ronaldsay, and the Mainland, all the more remarkable as the species is absent on mainland Great Britain.[85]

The coastline is well known for its colourful flowers including sea Aster, sea squill, sea thrift, common sea-lavender, bell and common heather. The Scottish primrose is found only on the coasts of Orkney and nearby Caithness and Sutherland.[63][83] Although stands of trees are generally rare, a small forest named Happy Valley with 700 trees and lush gardens was created from a boggy hillside near Stenness during the second half of the 20th century.[86]

The North Ronaldsay sheep is an unusual breed of domesticated animal, subsisting largely on a diet of seaweed, since they are confined to the foreshore for most of the year to conserve the limited grazing inland.[87]

Economy

The soil of Orkney is generally very fertile and most of the land is taken up by farms, agriculture being by far the most important sector of the economy and providing employment for a quarter of the workforce.[88] More than 90% of agricultural land is used for grazing for sheep and cattle, with cereal production utilising about 4% (10,000 acres) and woodland occupying only 330 acres.[89]

Fishing has declined in importance, but still employed 345 individuals in 2001, about 3.5% of the islands' economically active population, the modern industry concentrating on herring, white fish, lobsters, crabs and other shellfish, and salmon fish farming.[Notes 12]

Today, the traditional sectors of the economy export beef, cheese, whisky, beer, fish and other seafood. In recent years there has been growth in other areas including tourism, food and beverage manufacture, jewellery, knitwear, and other crafts production, construction and oil transportation through the Flotta oil terminal.[90] Retailing accounts for 17.5% of total employment,[89] and public services also play a significant role, employing a third of the islands' workforce.[91]

In 2007, of the 1,420 VAT registered enterprises 55% were in agriculture, forestry and fishing, 12% in manufacturing and construction, 12% in wholesale, retail and repairs, and 5% in hotels and restaurants. A further 5% were public service related.[89] 55% of these businesses employ between 5 and 49 people.[91]

Orkney has significant wind and marine energy resources, and renewable energy has recently come into prominence. The European Marine Energy Centre (EMEC) has installed a wave testing system at Billia Croo on the Orkney Mainland and a tidal power testing station on the island of Eday.[92] At the official opening of the Eday project the site was described as "the first of its kind in the world set up to provide developers of wave and tidal energy devices with a purpose-built performance testing facility."[Notes 13] Funding for the UK's first [[wave farm was announced in 2007. It will be the world's largest, with a capacity of 3 MW generated by four Pelamis machines at a cost of over £4 million.[94] During 2007 Scottish and Southern Energy plc in conjunction with the University of Strathclyde began the implementation of a Regional Power Zone in the Orkney archipelago. This scheme (that may be the first of its kind in the world) involves "active network management" that will make better use of the existing infrastructure and allow a further 15MW of new "non-firm generation" output from renewables onto the network.[95][96]

Transport

Air

The main airport in Orkney is Kirkwall Airport, with services to Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow and Inverness, as well as to Sumburgh Airport in Shetland.[97]

Within Orkney, the council operates airfields on most of the larger islands including Stronsay, Eday, North Ronaldsay, Westray, Papa Westray, and Sanday.[98] Reputedly the shortest scheduled air service in the world, between the islands of Westray and Papa Westray, is scheduled at two minutes duration[99] but can take less than one minute if the wind is in the right direction.

Ferries

Ferries serve both to link Orkney to Great Britain, and also to link together the various islands of Orkney. Ferry services operate between Orkney and the Scottish mainland and Shetland on the following routes:

- Gills Bay to St Margaret's Hope

- John o' Groats to Burwick on South Ronaldsay

- Lerwick to Kirkwall

- Aberdeen to Kirkwall

- Scrabster Harbour, Thurso to Stromness (operated by Northlink Ferries)

Between the islands, ferry services connect all the inhabited islands to Orkney Mainland.

Media

Orkney is served by two weekly local newspapers, The Orcadian and Orkney Today.[100]

A local BBC radio station, BBC Radio Orkney, the local opt-out of BBC Radio Scotland, broadcasts twice daily, with local news and entertainment.[101] Orkney also has a commercial radio station, The Superstation Orkney, which broadcasts to Kirkwall and parts of the mainland and also broadcasts to most of Caithness.[102] Moray Firth Radio broadcasts throughout Orkney on AM and from an FM transmitter just outside Thurso. The community radio station Caithness FM also broadcasts to Orkney.[103]

Language, literature and folklore

At the beginning of recorded history the islands were, it is believed, inhabited by the Picts, understood to speak a variety of the old British language from which Welsh is descended, although no written records survive. No certain knowledge of any pre-Pictish language exists anywhere in the north, and many suggestions have been made as to whether the ordinary people of the islands spoke Pictish or a proto-Celtic or indeed a non-Indo-European language. The Ogham script on the Buckquoy spindle-whorl is cited as evidence for the pre-Norse existence of Old Irish in Orkney.[104]

After the Norse occupation the place-names of Orkney became almost wholly West Norse.[105] The Norse language evolved into the local Norn, which lingered until the end of the 18th century, when it finally died out. Norn was replaced by the Orcadian dialect of Insular Scots. This dialect is at a low ebb due to the pervasive influences of television, education and the large number of incomers. However attempts are being made by some writers and radio presenters to revitalise its use[106] and the distinctive sing-song accent and many dialect words of Norse origin continue to be used.[Notes 14] The Orcadian word most frequently encountered by visitors is "peedie", meaning "small", which may be derived from the French petit.[108][Notes 15]

Orkney has a rich folklore and many of the former tales concern trows, an Orcadian form of troll that draws on the islands' Scandinavian connections.[110] Local customs in the past included marriage ceremonies at the Odin Stone that forms part of the Stones of Stenness.[111]

The best known literary figures from modern Orkney are the poet Edwin Muir, the poet and novelist George Mackay Brown and the novelist Eric Linklater.[112]

Orcadians

An Orcadian is a native of Orkney, a term that reflects a strongly held identity with a tradition of understatement.[113] Although the annexation of the earldom by Scotland took place over five centuries ago in 1472, most Orcadians regard themselves as Orcadians first and Scots second.[114]

When an Orcadian speaks of "Scotland", they are talking about the land to the immediate south of the Pentland Firth. When an Orcadian speaks of "the mainland", they mean Mainland, Orkney.[115] Tartan, clans, bagpipes and the like are traditions of the Scottish Highlands and are not a part of the islands' indigenous culture.[116] However, at least two tartans with Orkney connections have been registered and a tartan has been designed for Sanday by one of the island's residents,[117][118][119] and there are pipe bands in Orkney.[120][121]

Native Orcadians refer to the non-native residents of the islands as "ferry loupers", a term that has been in use for nearly two centuries at least.[122][Notes 16] This designation is celebrated in the Orkney Trout Fishing Association's "Ferryloupers Trophy", suggesting that although it can be used in a derogatory manner, it is more often a light-hearted expression.[123]

Outside links

| ("Wikimedia Commons" has material about Orkney) |

- Orknet

- Orkney.com The gateway to everything Orkney

- Orkneyjar, an Orcadian History and Heritage Site

- Spirit-of-Orkney, History and Heritage Site

- Vision of Britain - Groome Gazetteer entry for Orkney

- Orkney Islands Council, the local authority website

References

- ↑ The proto-Celtic root *φorko-, can mean either pig or salmon, thus giving an alternative of "island(s) of (the) salmon".[10]

- ↑ Thomson (2008) suggests that there may have been an element of Roman "boasting" involved, given that it was known to them that the Orcades lay at the northern extremity of the British Isles.[28] Similarly, Ritchie describes Tacitus' claims that Rome "conquered" Orkney as "a political puff, for there is no evidence of Roman military presence".[29]

- ↑ They were certainly politically organised. Ritchie notes the presence of an Orcadian ruler at the court of a Pictish high king at Inverness in 565 AD.[31]

- ↑ Sigurd The Mighty's son Gurthorm ruled for a single winter after Sigurd's death and died childless. Rognvald's son Hallad inherited the title but, unable to constrain Danish raids on Orkney, he gave up the earldom and returned to Norway, which according to the Orkneyinga Saga "everyone thought was a huge joke."[36]

- ↑ Sigurd the Stout was Thorfinn Skull-splitter's grandson.

- ↑ The first recorded bishop was Henry of Lund (also known as "the Fat") who was appointed at some time before 1035.[40] The bishopric appears to have been under the authority of the Archbishops of York and of Hamburg-Bremen at different times during the early period and from the mid twelfth century to 1472 was subordinate to the Archbishop of Nidaros (today's Trondheim).[41]

- ↑ The Scandinavian peoples, relatively recent converts to Christianity, had a tendency to confer martyrdom and sainthood on leading figures of the day who met violent deaths. Magnus and Haakon Paulsson had been co-rulers of Orkney, and although he had a reputation for piety, there is no suggestion that Magnus died for his Christian faith.[43]

- ↑ "St Magnus Cathedral still dominates the Kirkwall skyline - a familiar, and comforting sight, to Kirkwallians around the world."[44]

- ↑ It is often believed that the princess's death is associated with the village of St Margaret's Hope on South Ronaldsay but there is no evidence for this other than the co-incidence of the name.[48]

- ↑ Apparently without the knowledge of the Norwegian Rigsraadet (Council of the Realm), Christian pawned Orkney for 50,000 Rhenish guilders. On 28 May the next year he also pawned Shetland for 8,000 Rhenish guilders.[52] He had secured a clause in the contract which gave future kings of Norway the right to redeem the islands for a fixed sum of 210 kg of gold or 2,310 kg of silver. Several attempts were made during the 17th and 18th centuries to redeem the islands, without success.[53]

- ↑ For example at the Fall of Warness the tide can run at 4m/sec (7.8 knots).[65]

- ↑ Coull (2003) quotes the old saying that an Orcadian is a farmer with a boat, in contrast to a Shetlander, who is a fisherman with a croft.[56]

- ↑ "The centre offers developers the opportunity to test prototype devices in unrivalled wave and tidal conditions. Wave and tidal energy converters are connected to the National Grid via seabed cables running from open-water test berths. Testing takes place in a wide range of sea and weather conditions, with comprehensive round-the-clock monitoring."[93]

- ↑ Lamb (2003) counted 60 words "with correlates in Old Norse only" and 500 Scots expressions in common use in the 1950s.[107]

- ↑ The word is of uncertain origin and has also been attested in the Lothians and Fife in the 19th century.[109]

- ↑ The expression "ferry louper" has a literal meaning of "ferry jumper" i.e. one who has jumped off a ferry as distinct from a native.

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 336-403.

- ↑ Wickham-Jones (2007) p. 1 states there are 67 islands.

- ↑ Lamb, Raymond "Kirkwall" in Omand (2003)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 11-13.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Early Historical References to Orkney" Orkneyjar.com

- ↑ Tacitus (c. 98) Agricola. Chapter 10. "ac simul incognitas ad id tempus insulas, quas Orcadas vocant, invenit domuitque".

- ↑ Waugh, Doreen J. "Orkney Place-names" in Omand (2003) p. 116.

- ↑ Pokorny, Julius (1959) Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The Origin of Orkney" Orkneyjar.com. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

- ↑ "Proto-Celtic - English Word List" (pdf) (12 June 2002) University of Wales. p. 101.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 42.

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Laud Chronicle) (1066)

- ↑ "Hazelnut shell pushes back date of Orcadian site" (3 November 2007) Stone Pages Archaeo News. Retrieved 6 September 2009.

- ↑ "Skara Brae Prehistoric Village" Historic Scotland. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ↑ Moffat (2005) p. 154.

- ↑ Scotland: 2200-800 BC Bronze Age" worldtimelines.org.uk Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ↑ Ritchie, Graham "The Early Peoples" in Omand (2003) p. 32, 34.

- ↑ Wickham-Jones (2007) p. 73.

- ↑ Moffat (2005) pp. 154, 158, 161.

- ↑ Whittington, Graeme and Edwards, Kevin J. (1994) "Palynology as a predictive tool in archaeology" (pdf) Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 124 pp. 55–65.

- ↑ Wickham-Jones (2007) p. 74–76.

- ↑ Ritchie, Graham "The Early Peoples" in Omand (2003) p. 33.

- ↑ Wickham-Jones (2007) pp. 81-84.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael (2007) Burroughston Broch. The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ↑ Ritchie, Graham "The Early Peoples" in Omand (2003) pp. 35-37.

- ↑ Crawford, Iain "The wheelhouse" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 118-22.

- ↑ Moffat (2005) pp. 173-5.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 4-5

- ↑ Ritchie, Graham "The Early Peoples" in Omand (2003) p. 36

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Thomson (2008) pp. 4-6.

- ↑ Ritchie, Anna "The Picts" in Omand (2003) p. 39

- ↑ Ritchie, Anna "The Picts" in Omand (2003) pp. 42-46.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 43-50.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 24.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 29.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 30 quoting chapter 5.

- ↑ Wenham, Sheena "The South Isles" in Omand (2003) p. 211.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 56-58.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 69. quoting the Orkneyinga Saga chapter 12.

- ↑ Watt, D.E.R., (ed.) (1969) Fasti Ecclesia Scoticanae Medii Aevii ad annum 1638. Scottish Records Society. p. 247.

- ↑ "The Diocese of Orkney" Firth's Celtic Scotland. Retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ↑ Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) pp. 66-68.

- ↑ Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) p. 69.

- ↑ "St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall" Orkneyar. Retrieved 10 September 2009.

- ↑ Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) p. 64.

- ↑ Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) pp. 72-73.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 134-37.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Thompson (2008) pp. 146-47.

- ↑ Thompson (2008) p. 160.

- ↑ Armit (2006) pp. 173–76.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) p. 40.

- ↑ "Diplom fra Shetland datert 24.november 1509" University Library, University in Bergen. (Norwegian). Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ "Norsken som døde" Universitas, Norsken som døde (Norwegian) Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Thompson (2008) p. 183.

- ↑ Crawford, Barbara E. "Orkney in the Middle Ages" in Omand (2003) pp. 78-79.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Coull, James "Fishing" in Omand (2003) pp. 144-55.

- ↑ Thompson (2008) pp. 371-72.

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 364-65.

- ↑ Thomson, William P. L. "Agricultural Improvement" in Omand (2003) pp. 93, 99.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 434-36.

- ↑ Thomson (2008) pp. 439-43.

- ↑ Whitakers (1990) pp. 611, 614.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Brown, John Flett "Geology and Landscape" in Omand (2003) p. 19.

- ↑ "The Sorcerous Finfolk" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "Fall of Warness Test Site " EMEC. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "The Big Tree, Orkney". Forestry Commission. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ Shearer, Lorraine. "Exhibition will tell story of the Boy's Ploughing Match". The Orcadian. http://www.orcadian.co.uk/features/articles/ploughingmatch.htm. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ↑ Marshall, J.E.A., & Hewett, A.J. "Devonian" in Evans, D., Graham C., Armour, A., & Bathurst, P. (eds) (2003) The Millennium Atlas: petroleum geology of the central and northern North Sea.

- ↑ Hall, Adrian and Brown, John (September 2005) "Basement Geology". Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ↑ Hall, Adrian and Brown, John (September 2005) "Lower Middle Devonian". Retrieved 10 November 2008.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Brown, John Flett "Geology and Landscape" in Omand (2003) pp. 4-5.

- ↑ Mykura, W. (with contributions by Flinn, D. & May, F.) (1976) British Regional Geology: Orkney and Shetland. Institute of Geological Sciences. Natural Environment Council.

- ↑ Land Use Consultants (1998) "Orkney landscape character assessment". Scottish Natural Heritage Review No. 100.

- ↑ Odling, N.W.A. (2000) "Point of Ayre". (pdf) "Caledonian Igneous Rocks of Great Britain: Late Silurian and Devonian volcanic rocks of Scotland". Geological Conservation Review 17 : Chapter 9, p. 2731. JNCC. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ↑ Hall, Adrian and Brown, John (September 2005) "Orkney Landscapes: Permian dykes" Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ↑ Brown, John Flett "Geology and Landscape" in Omand (2003) p. 10.

- ↑ Chalmers, Jim "Agriculture in Orkney Today" in Omand (2003) p. 129.

- ↑ "Regional mapped climate averages" Met Office. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "The Climate of Orkney" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "About the Orkney Islands". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "Sunrise and Sunsets" The Orcadian. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- ↑ John Vetterlein (21 December 2006). "Sky Notes: Aurora Borealis Gallery". http://www.orcadian.co.uk/skynotes/aurora.htm. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 "Northern Isles". SNH. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ↑ Benvie (2004) pp. 126–38.

- ↑ Haynes, S., Jaarola M., & Searle, J. B. (2003). "Phylogeography of the common vole (Microtus arvalis) with particular emphasis on the colonization of the Orkney archipelago" (abstract page). Molecular Ecology 12: 951–956. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01795.x. PMID 12753214. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01795.x. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ↑ "Boggy hillside reborn as Orkney forest reserve". ( 27 May 2011) BBC. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "North Ronaldsay". Sheep Breeds. Seven Sisters Sheep Centre. http://www.sheepcentre.co.uk/sheep_breeds.htm. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- ↑ Chalmers, Jim "Agriculture in Orkney Today" in Omand (2003) p. 127, 133 quoting the Scottish Executive Agricultural Census of 2001 and stating that 80% of the land area is farmed if rough grazing is included.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 "Orkney Economic Review No. 23." (2008) Kirkwall. Orkney Islands Council.

- ↑ "Business Directory" Orkney Islands Council. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 "Orkney Economic Update" (1999) (pdf) HIE. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ "European Marine Energy Centre". http://www.emec.org.uk/. Retrieved 3 February 2007.

- ↑ Highlands and Islands Enterprise (28 September 2007). "First Minister Opens New Tidal Energy Facility at EMEC". Press release. http://www.allmediascotland.com/media_releases/1687/first_minister_opens_new_tidal_energy_facility_at_emec. Retrieved 1 October 2007.

- ↑ "Orkney to get 'biggest' wave farm" BBC News. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- ↑ Registered Power Zone Annual Report for period 1 April 2006 to 31 March 2007 (pdf) Scottish Hydro Electric Power Distribution and Southern Electric Power Distribution. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ↑ Facilitate generation connections on Orkney by automatic distribution network management (pdf) DTI. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ↑ "Getting Here" Visit Orkney. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ "Air Travel" Orkney Islands Council. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ "Getting Here" Westray and Papa Westray Craft and Tourist Associations. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- ↑ "Orkney Today" Orkney Today. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ↑ "Radio Orkney". BBC. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "Superstation Orkney" thesuperstation.co.uk. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "Welcome to the Caithness FM website" Caithness FM. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ Forsyth, Katherine (1995). "The ogham-inscribed spindle-whorl from Buckquoy: evidence for the Irish language in pre-Viking Orkney?" (PDF). The Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (ARCHway) 125: 677–96. http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/PSAS_2002/pdf/vol_125/125_677_696.pdf. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ↑ Lamb, Gregor (1995) Testimony of the Orkneyingar: Place Names of Orkney. Byrgisey. ISBN 0-9513443-4-X

- ↑ "The Orcadian Dialect" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ↑ Lamb, Gregor "The Orkney Tongue" in Omand (2003) pp. 250-53.

- ↑ Clackson, Stephen (25 November 2004) The Orcadian. Kirkwall.

- ↑ Grant, W. and Murison, D.D. (1931-1976) Scottish National Dictionary. Scottish National Dictionary Association. ISBN 0080345182.

- ↑ "The Trows". Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ Muir, Tom "Customs and Traditions" in Omand (2003) p. 270.

- ↑ Drever, David "Orkney Literature" in Omand (2003) p. 257.

- ↑ "The Orcadians - The people of Orkney" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "'We are Orcadian first, and Scottish second' many people would tell me during the course of my fieldwork." McClanahan, Angela (2004) The Heart of Neolithic Orkney in its Contemporary Contexts: A case study in heritage management and community values. Historic Scotland/University of Manchester, p. 25 (§3.47) [1] Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ↑ "Where is Orkney?" Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ Orkneyjar FAQ Orkneyjar. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "Orkney tartan" tartans.scotland.net Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "Sanday Tartan" www.clackson.com. Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- ↑ "Clackson tartan" tartans.scotland.net. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "Kirkwall City Pipe Band" kirkwallcity.com. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ "Stromness RBL Pipe Band" stromnesspipeband.co.uk. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ↑ Vedder, David (1832) Orcadian Sketches. Edinburgh. William Tait.

- ↑ "2009 Competition Programme" Orkney Trout Fishing Association. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- Armit, Ian (2006) Scotland's Hidden History. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 075243764X

- Benvie, Neil (2004) Scotland's Wildlife. London. Aurum Press. ISBN 1854109782

- Ballin Smith, B. and Banks, I. (eds) (2002) In the Shadow of the Brochs, the Iron Age in Scotland. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 075242517X

- Clarkson, Tim (2008) The Picts: A History. Stroud. The History Press. ISBN 9780752443928

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 1841954543.

- Moffat, Alistair (2005) Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500051337

- Omand, Donald (ed.) (2003) The Orkney Book. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1841582549

- Thomson, William P. L. (2008) The New History of Orkney. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 9781841586960

- Whitaker's Almanack 1991 (1990). London. J. Whitaker & Sons. ISBN 0850212057

- Wickham-Jones, Caroline (2007) Orkney: A Historical Guide. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1841585963

Books

- Fresson, Captain E. E. Air Road to the Isles. (2008) Kea Publishing. ISBN 9780951895894

- Lo Bao, Phil and Hutchison, Iain (2002) BEAline to the Islands. Kea Publishing. ISBN 9780951895849

- Warner, Guy (2005) Orkney by Air. Kea Publishing. ISBN 9780951895870

- Batey, C.E. et al (eds.) (1995) The Viking Age in Caithness, Orkney and the North Atlantic. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748606320

| Counties of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

Aberdeen • Anglesey • Angus • Antrim • Argyll • Armagh • Ayr • Banff • Bedford • Berks • Berwick • Brecknock • Buckingham • Bute • Caernarfon • Caithness • Cambridge • Cardigan • Carmarthen • Chester • Clackmannan • Cornwall • Cromarty • Cumberland • Denbigh • Derby • Devon • Dorset • Down • Dumfries • Dunbarton • Durham • East Lothian • Essex • Fermanagh • Fife • Flint • Glamorgan • Gloucester • Hants • Hereford • Hertford • Huntingdon • Inverness • Kent • Kincardine • Kinross • Kirkcudbright • Lanark • Lancaster • Leicester • Lincoln • Londonderry • Merioneth • Middlesex • Midlothian • Monmouth • Montgomery • Moray • Nairn • Norfolk • Northampton • Northumberland • Nottingham • Orkney • Oxford • Peebles • Pembroke • Perth • Radnor • Renfrew • Ross • Roxburgh • Rutland • Selkirk • Shetland • Salop • Somerset • Stafford • Stirling • Suffolk • Surrey • Sussex • Sutherland • Tyrone • Warwick • West Lothian • Westmorland • Wigtown • Wilts • Worcester • York |