Devon: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

More material |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

|name=Devon | |name=Devon | ||

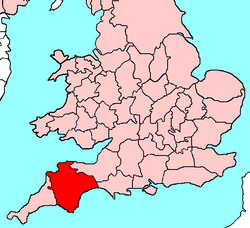

|map image=DevonBrit5.PNG | |map image=DevonBrit5.PNG | ||

|flag=FlagOfDevon.PNG | |||

|picture= Ilfracombe.jpg | |picture= Ilfracombe.jpg | ||

|picture caption= Ilfracombe | |picture caption= Ilfracombe | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

|biggest town=[[Plymouth]] | |biggest town=[[Plymouth]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

'''Devon''' or '''Devonshire''' is a large [[Counties of the United Kingdom|shire]] lying in the southwest of [[Great Britain]]. Devon stands between two seas, the [[Bristol Channel]] washing its north coast and the [[English Channel]] its south coast. To the west lies [[Cornwall]], and to the east [[Dorset]] and [[Somerset]]. The centre of Devonshire has rolling hills, the south of the county dominated by [[Dartmoor]]. | |||

Devon is | Though modest in population, Devon is one of the largest of the British counties in area, only six are larger, and in that area are some of the finest wild landscapes in the land. | ||

{{ | The [[county town]] is the cathedral city of [[Exeter]] in the southeast and its largest town the port city of [[Plymouth]] in the southwest. Those are the only large towns by national standards, but throughout are found several pretty smaller towns and countless farming and fishing villages. Much of the county is rural and includes one national park, [[Dartmoor]], and part of another, [[Exmoor]]. | ||

The boundary with Cornwall is marked by the [[River Tamar]] almost from coast to coast, apart from a narrow salient along the [[River Ottery]] north of [[Launceston]], bringing [[North Petherwin]] and neighbouring hamlets into Devon though west of the Tamar. | |||

==Name of the county== | |||

The name ''Devon'' derives from the name of the tribe which inhabited the southwestern peninsula of Britain at the time of the Roman invasion around 50 AD, known as the ''Dumnonii'', thought to mean in the British tongue "deep valley dwellers". In Old English, the men of Devon were the ''Defnas'' and their shire ''Defnascir''. In Welsh, Devon is known as ''Dyfnaint'' and across the sea the Bretons call it ''Devnent''. | |||

William Camden, in his 1607 edition of ''Britannia'', described Devon as being one part of an older, wider country that once included Cornwall: | |||

<blockquote>THAT region which, according to the Geographers, is the first of all Britaine, and, growing straiter still and narrower, shooteth out farthest into the West, […] was in antient time inhabited by those Britans whom Solinus called Dunmonii, […] But the Country of this nation is at this day divided into two parts, knowen by later names of Cornwall and Denshire, […]<ref>|William Camden, ''Britannia''.</ref></blockquote> | |||

==Landscape== | |||

[[File:Beach at Lee Bay - geograph.org.uk - 1421688.jpg|right|thumb|230px|Lee Bay]] | |||

The county is home to part of England's only natural UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Dorset and East Devon Coast, known as the Jurassic Coast for its geology and geographical features. It is also home to Braunton Burrows UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, a dune complex in the north of the county. Along with its neighbour, Cornwall, Devon is known as the "Cornubian massif". This geology gives rise to the landscapes of [[Bodmin Moor]], [[Dartmoor]] and [[Exmoor]], the latter two being national parks. Devon has seaside resorts and historic towns and cities, rural scenery and a mild climate, accounting for the large tourist sector of its economy. | |||

[[File:Heath.jpg|right|thumb|230px|Heathland at Woodbury Common, SE Devon]] | |||

===Geology=== | |||

The principal geological formations of Devon are the "Devonian" (in north Devon, south Devon and extending into Cornwall), the granite batholith of Dartmoor in central Devon; and the Culm Measures (also extending into north Cornwall). There are small remains of pre-Devonian rocks on the south Devon coast.<ref>Edmonds, E. A., et al. (1975) ''South-West England''; based on previous editions by H. Dewey (British Geological Survey UK Regional Geology Guide series no. 17, 4th ed.) London: HMSO ISBN 0-11-880713-7</ref> | |||

Devon gave its name to a geological period: the Devonian period, so named because of the abundance of the grey limestone found there. It was Roderick Murchison and Adam Sedgwick who originally named the Devonian Period following research they carried out in Devon, and in particular, Torbay. They found some unusual marine fossils in the limestone at Lummaton Quarry and it was this discovery that lead to the time period becoming known globally as the Devonian. | |||

The whole of central Devon is occupied by [[Dartmoor]], the largest area of igneous rock in South West England. Geologists believe that Dartmoor, Bodmin Moor and the [[Isles of Scilly]], along with other granite outcrops in Devon and Cornwall, are the surfacing of one gigantic granite rock or basolith. | |||

Another major rock system is the '''Culm Measures''', a geological formation of the Carboniferous period that occurs principally in Devon and Cornwall. The measures are so called either from the occasional presence of a soft, sooty coal, which is known in Devon as ''culm'', or from the contortions commonly found in the beds.<ref>{{cite book|last=Edmonds|first=E. A.|coauthors=McKeown, M. C.; Williams, M.|others=Dewey, H.|title=South-West England|publisher=HMSO/British Geological Survey|location=London|year=1975|edition=4th|series=British Regional Geology|page=34|chapter=Carboniferous Rocks|isbn=0118807137}}</ref> This formation stretches from [[Bideford]] to [[Bude]] in Cornwall, and contributes to a gentler, greener, more rounded landscape. It is also found on the western, north and eastern borders of Dartmoor. | |||

===Coasts=== | |||

[[File:Road climbing out of Lynmouth. - geograph.org.uk - 74169.jpg|thumb|230px|Near Lynmouth, on the coast of North Devon]] | |||

Devon is the only British county outside the [[Highlands|Scottish Highlands]] to have two separate coastlines, on the Bristol Channel to the north and on the English Channel to the south. The coasts have very different characters: the north coast, battered by Atlantic storms, is marked with high cliffs and precipitous narrow valleys, while the south coast is gentler, sliced through with broad inlets and long tidal creeks, both revealing at low tide vast mudflats. Both coasts have their pretty fishing villages, the sheltered creeks of the south coast dotted with a profusion of them and with havens for pleasure yachts. | |||

The South West Coast Path runs along the entire length of both coast, about 65% of which is named as "Heritage Coast".<ref>Dewey, Henry (1948) ''British Regional Geology: South West England'', 2nd ed. London: H.M.S.O.</ref> | |||

The island of [[Lundy]] and the Eddystone Rocks also belong to Devon. | |||

===Moorland and inland Devon=== | |||

The [[Dartmoor]] National Park lies wholly in Devon, and the [[Exmoor]] National Park lies in both Devon and [[Somerset]]. Apart from these areas of high moorland the county has attractive rolling rural scenery and villages with thatched cob cottages. All these features make Devon a popular holiday destination. | |||

===South Devon=== | |||

[[File:Salcombe estuary from Sharpitor.jpg|right|thumb|230px|Salcombe]] | |||

Southern Devon has a landscape of rolling hills dotted with small towns, such as [[Dartmouth]], [[Ivybridge]], [[Kingsbridge]], [[Salcombe]], and [[Totnes]]. The towns of [[Torquay]] and [[Paignton]] are the principal seaside resorts on the south coast. Eastern Devon has the first seaside resort to be developed in the county, [[Exmouth]] and the more upmarket Georgian town of [[Sidmouth]]. Exmouth marks the western end of the [[Jurassic Coast]] World Heritage Site. Another notable feature is the coastal railway line between Newton Abbot and the Exe Estuary: the red sandstone cliffs and sea views are very dramatic and in the resorts railway line and beaches are very near. | |||

===North Devon=== | |||

[[File:No 62, Clovelly - geograph.org.uk - 984976.jpg|right|thumb|140px|Clovelly]] | |||

North Devon is very rural with few major towns except [[Barnstaple]], [[Great Torrington]], [[Bideford]] and [[Ilfracombe]]. Devon's Exmoor coast has the highest cliffs in southern Britain, culminating in the Great Hangman, a 1,043 foot "hog's-back" hill with an 820 foot cliff-face, located near Combe Martin Bay.<ref>http://www.exmoor-nationalpark.gov.uk/index/learning_about/moor_facts.htm|Exmoor National Park, National Park Facts |accessdate=2009-05-10</ref> Its sister cliff is the 218 m (716 ft) Little Hangman, which marks the western edge of coastal Exmoor. One of the features of the North Devon coast is that [[Bideford Bay]] and the [[Hartland Point]] peninsula are both west-facing, Atlantic facing coastlines; so that a combination of an off-shore (east) wind and an Atlantic swell produce excellent surfing conditions. The beaches of Bideford Bay ([[Woolacombe]], [[Saunton]], [[Westward Ho!]] and [[Croyde]]), along with parts of North Cornwall and South Wales, are the main centres of surfing in Britain. | |||

[[File:Devon fields stitch.jpg|left|thumb|800px|Fields in south Devon after a snowfall]] | |||

{{clear}} | |||

===Birds, beasts and blooms=== | |||

[[File:Pnies5.jpg|thumb|right|220px|Ponies grazing on Exmoor near Brendon, North Devon]] | |||

The variety of habitats means that there is a wide range of wildlife. A popular challenge among birders is to find over 100 species in the county in a day. The county's wildlife is protected by several wildlife charities such as the Devon Wildlife Trust, a charity which looks after 40 nature reserves. The Devon Bird Watching and Preservation Society is a county bird society with a long and distinguished history dating back to 1928. It is dedicated to the study and conservation of wild birds looks after several areas, such as Beesands Ley. There is also the RSPB, which has reserves in the county, as well as English Nature, who look after several reserves such as Dawlish Warren. | |||

The botany of the county is very diverse and includes some rare species not found elsewhere in the British Isles other than Cornwall. Botanical reports begin in the 17th century and there is a ''Flora Devoniensis'' by Jones and Kingston in 1829, and a ''Flora of Devon'' in 1939 by Keble Martin and Fraser.<ref>Jones, John Pike & Kingston, J. F. (1829) ''Flora Devoniensis''. 2 pts, in 1 vol. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green</ref><ref>Martin, W. Keble & Fraser, G. T. (eds.) (1939) Flora of Devon. Arbroath</ref> There is a general account by W. P. Hiern and others in ''The Victoria History of the County of Devon'', vol. 1 (1906); pp. 55–130, with map. Devon is divided into two Watsonian vice-counties: north and south, the boundary being an irregular line approximately across the higher part of Dartmoor and then along the canal eastwards. | |||

Rising temperatures have led to Devon becoming the first place in modern Britain to cultivate olives commercially.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/weather/article1785059.ece|title=Britain warms to the taste for home-grown olives|author=Paul Simons|publisher=Times Online|accessdate=2007-09-20|date=2007-05-14 | location=London}}</ref> | |||

==History== | |||

===Human occupation=== | |||

Kents Cavern in Torquay had produced human remains from 30-40,000 years ago. Dartmoor is thought to have been occupied by Mesolithic hunter-gatherer peoples from about 6,000 BC. The Romans held the area under military occupation for around 350 years. Later, the area became a frontier between Welsh Dumnonia and English [[Wessex]], and it was largely absorbed into Wessex by the mid 9th century. According to William of Malmesbury, the border with Cornwall was set by King Athelstan on the east bank of the River Tamar in 936, though historians doubt that Cornwall was absorbed so late; King Athelstan's grandfather King Alfred had several estates there. | |||

Devon's seagoing tradition provided many of the heroes of the heroic age of the sea. Sir Francis Drake was born outside [[Tavistock]] and built his mansion not far off. The ships which fought the Spanish Armada sailed from [[Plymouth]] manned by men of Devon, as did all the great sea adventures. | |||

Devon has also featured in most of the civil conflicts in England since the Norman Conquest, including the Wars of the Roses, Perkin Warbeck's rising in 1497, the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549, and the English Civil War. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 began with the landing of William of Orange at [[Brixham]]. | |||

Devon has produced tin, copper and other metals from ancient times. Devon's tin miners enjoyed a substantial degree of independence through Devon's Stannary Parliament, which dates back to the 12th century. The last recorded sitting was in 1748.<ref>{{cite web | |||

|url=http://users.senet.com.au/~dewnans/Devon_Stannary_History.html | |||

|title=Devon's Mining History and Stannary parliament | |||

|publisher=users.senet.com.au | |||

|accessdate=2008-03-29}}</ref> | |||

==Economy and industry== | |||

Devon is disadvantaged economically compared to other parts of southern England, owing to the decline of a number of core industries, notably fishing, mining and farming. Consequently, most of Devon has qualified for the European Community Objective 2 status. Agriculture has been an important industry in Devon since the 19th century.<ref>[http://www.swcore.co.uk/southwest.htm], South West Chamber of Rural Enterprise</ref> The 2001 foot and mouth crisis harmed the farming community severely.<ref>''In Devon, the county council estimated that 1,200 jobs would be lost in agriculture and ancillary rural industries'' — [http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200001/cmhansrd/vo010425/debtext/10425-17.htm#column_357 ''Hansard'', 25th April 2001]</ref> | |||

[[File:torquay.devon.750pix.jpg|thumb|left|230px|Torquay seafront at high tide]] | |||

The attractive lifestyle of the area is drawing in new industries which are not heavily dependent upon geographical location; [[Dartmoor]], for instance, has recently seen a significant rise in the percentage of its inhabitants involved in the financial services sector. In 2003, the Meteorological Office, the United Kingdom's national and international weather service, moved to Exeter. Devon is one of the rural counties, with the advantages and challenges characteristic of these. Despite this, the county's economy is also heavily influenced by its two main urban centres, Plymouth and Exeter. | |||

Since the rise of seaside resorts with the arrival of the railways in the 19th century, Devon's economy has been heavily reliant on tourism. The county's economy has followed the declining trend of British seaside resorts since the mid-20th century, with some recent revival. This revival has been aided by the designation of much of Devon's countryside and coastline as the [[Dartmoor]] and [[Exmoor]] national parks, and the [[Jurassic Coast]] and Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Sites. In 2004 the county's tourist revenue was £1.2 billion. | |||

==Hundreds== | |||

Devon is divided into 32 hundreds:<ref>GENUKI http://genuki.cs.ncl.ac.uk/DEV/Hundreds.html</ref> | |||

{| | |||

| | |||

*Axminster | |||

*Bampton | |||

*Black Torrington | |||

*Braunton | |||

*Cliston | |||

*Coleridge | |||

*Colyton | |||

*Crediton | |||

| | |||

*East Budleigh | |||

*Ermington | |||

*Exminster | |||

*Fremington | |||

*Halberton | |||

*Hartland | |||

*Hayridge | |||

*Haytor | |||

| | |||

*Hemyock | |||

*Lifton | |||

*North Tawton and Winkleigh | |||

*Ottery | |||

*Plympton | |||

*Roborough | |||

*Shebbear | |||

*Shirwell | |||

| | |||

*South Molton | |||

*Stanborough | |||

*Tavistock | |||

*Teignbridge | |||

*Tiverton | |||

*West Budleigh | |||

*Witheridge | |||

*Wonford | |||

|} | |||

==Towns and villages== | |||

[[File:devon.brixham.750pix.jpg|thumb|right|220px|Brixham's inner harbour at low tide]] | |||

The greatest towns of Devon are its two cities: Plymouth, a historic port and the largest town of the southwest, and [[Exeter]], the [[county town]]. [[Torbay]] too has grown into a substantial conurbation centred on [[Torquay]]. | |||

Devon's coast is lined with tourist resorts, many of which grew rapidly with the arrival of the railways in the 19th century. Examples include [[Dawlish]], [[Exmouth]] and [[Sidmouth]] on the south coast, and [[Ilfracombe]] and [[Lynmouth]] on the north. The [[Torbay]] conurbation of [[Torquay]], [[Paignton]] and [[Brixham]] on the south coast is perhaps the largest and most popular of these resorts. | |||

Rural market towns in the county include [[Axminster]], [[Barnstaple]], [[Bideford]], [[Honiton]], [[Newton Abbot]], [[Okehampton]], [[Tavistock, Devon|Tavistock]], [[Totnes]] and [[Tiverton]]. | |||

==Place names and customs== | |||

[[File:westwardho.beach.arp.750pix.jpg|thumb|220px|The beach at Westward Ho!, North Devon]] | |||

Devon's place names are a mixture of English and the British tongue (or Old Welsh) which was the speech of the land before the Anglo-Saxons came. | |||

Many with the endings "coombe/combe" and "tor" – Coombe being the British word for "valley" or hollow (as the Welsh 'cwm') whilst "tor" derives from a number of Celtic loan-words in English (Old Welsh ''twrr'' and Gaelic ''tòrr'') and is used as a name for the formations of rocks found on the moorlands. Its frequency is greatest in Devon, where it is the second most common place name component (after 'ton', derived from the Old English ''tun'' meaning enclosure, farmstead, farm or village). | |||

River names, such as the [[River Exe|Exe]], [[River Axe|Axe]], [[River Tavy|Tavy]], [[River Tamar|Tamar]] and [[River Taw|Taw]] are from common British or earlier roots, while smaller local rivers have taken English names. | |||

[[Westward Ho!]] has the distinction unique in Britain of having an exclamation mark in its name: its name derives from that of a novel. | |||

Devon has a variety of festivals and traditional practices, including the traditional orchard-visiting Wassail in [[Whimple]] every 17 January and the carrying of flaming tar barrels in [[Ottery St Mary]] on 5 November each year, where people who have lived in Ottery for long enough are called upon to celebrate Bonfire Night by running through the village (and the gathered crowds) with flaming barrels of tar on their backs.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/devon/discovering/legends/ottery_tar_barrels.shtml|title=Ottery Tar Barrels|publisher=BBC|accessdate=2008-05-14}}</ref> Berry Pomeroy still celebrates "Queen's Day" for Elizabeth I. | |||

==Food== | |||

The county has given its name to a number of culinary specialities. Food from the sea and food from the field are found in abundance. | |||

The Devonshire cream tea, involving scones, jam and clotted cream, is thought to have originated in Devon (though claims have also been made for neighbouring counties); in other countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, it is known as a "Devonshire tea".<ref>Mason, Laura; Brown, Catherine (1999) From Bath Chaps to Bara Brith. Totnes: Prospect Books</ref><ref>Pettigrew, Jane (2004) Afternoon Tea. Andover: Jarrold</ref><ref>Fitzgibbon, Theodora (1972) A Taste of England: the West Country. London: J. M. Dent</ref> | |||

==Outside links== | |||

*[http://www.bbc.co.uk/devon/ BBC Devon] | |||

*[http://www.cs.ncl.ac.uk/genuki/DEV/ Genuki Devon] Historical, geographical and genealogical information | |||

==References== | |||

{{Reflist}} | |||

==Further reading== | |||

*Oliver, George (1846) ''Monasticon Dioecesis Exoniensis'': being a collection of records and instruments illustrating the ancient conventual, collegiate, and eleemosynary foundations, in the Counties of Cornwall and Devon, with historical notices, and a supplement, comprising a list of the dedications of churches in the Diocese, an amended edition of the taxation of Pope Nicholas, and an abstract of the Chantry Rolls [with supplement and index]. Exeter: P. A. Hannaford, 1846, 1854, 1889 | |||

*Pevsner, N. (1952) ''North Devon'' and ''South Devon'' (Buildings of England). 2 vols. Penguin Books | |||

*Stabb, John ''Some Old Devon Churches: their rood screens, pulpits, fonts, etc.''. 3 vols. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent, 1908, 1911, 1916 | |||

{{British county}} | {{British county}} | ||

Revision as of 17:57, 26 August 2011

| Devon United Kingdom | |

Ilfracombe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Flag | |

| Auxilio Divino (By divine aid) | |

| |

| [Interactive map] | |

| Area: | 2,405 square miles |

| Population: | 1,133,463 |

| County town: | Exeter |

| Biggest town: | Plymouth |

| County flower: | Primrose [2] |

Devon or Devonshire is a large shire lying in the southwest of Great Britain. Devon stands between two seas, the Bristol Channel washing its north coast and the English Channel its south coast. To the west lies Cornwall, and to the east Dorset and Somerset. The centre of Devonshire has rolling hills, the south of the county dominated by Dartmoor.

Though modest in population, Devon is one of the largest of the British counties in area, only six are larger, and in that area are some of the finest wild landscapes in the land.

The county town is the cathedral city of Exeter in the southeast and its largest town the port city of Plymouth in the southwest. Those are the only large towns by national standards, but throughout are found several pretty smaller towns and countless farming and fishing villages. Much of the county is rural and includes one national park, Dartmoor, and part of another, Exmoor.

The boundary with Cornwall is marked by the River Tamar almost from coast to coast, apart from a narrow salient along the River Ottery north of Launceston, bringing North Petherwin and neighbouring hamlets into Devon though west of the Tamar.

Name of the county

The name Devon derives from the name of the tribe which inhabited the southwestern peninsula of Britain at the time of the Roman invasion around 50 AD, known as the Dumnonii, thought to mean in the British tongue "deep valley dwellers". In Old English, the men of Devon were the Defnas and their shire Defnascir. In Welsh, Devon is known as Dyfnaint and across the sea the Bretons call it Devnent.

William Camden, in his 1607 edition of Britannia, described Devon as being one part of an older, wider country that once included Cornwall:

THAT region which, according to the Geographers, is the first of all Britaine, and, growing straiter still and narrower, shooteth out farthest into the West, […] was in antient time inhabited by those Britans whom Solinus called Dunmonii, […] But the Country of this nation is at this day divided into two parts, knowen by later names of Cornwall and Denshire, […][1]

Landscape

The county is home to part of England's only natural UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Dorset and East Devon Coast, known as the Jurassic Coast for its geology and geographical features. It is also home to Braunton Burrows UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, a dune complex in the north of the county. Along with its neighbour, Cornwall, Devon is known as the "Cornubian massif". This geology gives rise to the landscapes of Bodmin Moor, Dartmoor and Exmoor, the latter two being national parks. Devon has seaside resorts and historic towns and cities, rural scenery and a mild climate, accounting for the large tourist sector of its economy.

Geology

The principal geological formations of Devon are the "Devonian" (in north Devon, south Devon and extending into Cornwall), the granite batholith of Dartmoor in central Devon; and the Culm Measures (also extending into north Cornwall). There are small remains of pre-Devonian rocks on the south Devon coast.[2]

Devon gave its name to a geological period: the Devonian period, so named because of the abundance of the grey limestone found there. It was Roderick Murchison and Adam Sedgwick who originally named the Devonian Period following research they carried out in Devon, and in particular, Torbay. They found some unusual marine fossils in the limestone at Lummaton Quarry and it was this discovery that lead to the time period becoming known globally as the Devonian.

The whole of central Devon is occupied by Dartmoor, the largest area of igneous rock in South West England. Geologists believe that Dartmoor, Bodmin Moor and the Isles of Scilly, along with other granite outcrops in Devon and Cornwall, are the surfacing of one gigantic granite rock or basolith.

Another major rock system is the Culm Measures, a geological formation of the Carboniferous period that occurs principally in Devon and Cornwall. The measures are so called either from the occasional presence of a soft, sooty coal, which is known in Devon as culm, or from the contortions commonly found in the beds.[3] This formation stretches from Bideford to Bude in Cornwall, and contributes to a gentler, greener, more rounded landscape. It is also found on the western, north and eastern borders of Dartmoor.

Coasts

Devon is the only British county outside the Scottish Highlands to have two separate coastlines, on the Bristol Channel to the north and on the English Channel to the south. The coasts have very different characters: the north coast, battered by Atlantic storms, is marked with high cliffs and precipitous narrow valleys, while the south coast is gentler, sliced through with broad inlets and long tidal creeks, both revealing at low tide vast mudflats. Both coasts have their pretty fishing villages, the sheltered creeks of the south coast dotted with a profusion of them and with havens for pleasure yachts.

The South West Coast Path runs along the entire length of both coast, about 65% of which is named as "Heritage Coast".[4]

The island of Lundy and the Eddystone Rocks also belong to Devon.

Moorland and inland Devon

The Dartmoor National Park lies wholly in Devon, and the Exmoor National Park lies in both Devon and Somerset. Apart from these areas of high moorland the county has attractive rolling rural scenery and villages with thatched cob cottages. All these features make Devon a popular holiday destination.

South Devon

Southern Devon has a landscape of rolling hills dotted with small towns, such as Dartmouth, Ivybridge, Kingsbridge, Salcombe, and Totnes. The towns of Torquay and Paignton are the principal seaside resorts on the south coast. Eastern Devon has the first seaside resort to be developed in the county, Exmouth and the more upmarket Georgian town of Sidmouth. Exmouth marks the western end of the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site. Another notable feature is the coastal railway line between Newton Abbot and the Exe Estuary: the red sandstone cliffs and sea views are very dramatic and in the resorts railway line and beaches are very near.

North Devon

North Devon is very rural with few major towns except Barnstaple, Great Torrington, Bideford and Ilfracombe. Devon's Exmoor coast has the highest cliffs in southern Britain, culminating in the Great Hangman, a 1,043 foot "hog's-back" hill with an 820 foot cliff-face, located near Combe Martin Bay.[5] Its sister cliff is the 218 m (716 ft) Little Hangman, which marks the western edge of coastal Exmoor. One of the features of the North Devon coast is that Bideford Bay and the Hartland Point peninsula are both west-facing, Atlantic facing coastlines; so that a combination of an off-shore (east) wind and an Atlantic swell produce excellent surfing conditions. The beaches of Bideford Bay (Woolacombe, Saunton, Westward Ho! and Croyde), along with parts of North Cornwall and South Wales, are the main centres of surfing in Britain.

Birds, beasts and blooms

The variety of habitats means that there is a wide range of wildlife. A popular challenge among birders is to find over 100 species in the county in a day. The county's wildlife is protected by several wildlife charities such as the Devon Wildlife Trust, a charity which looks after 40 nature reserves. The Devon Bird Watching and Preservation Society is a county bird society with a long and distinguished history dating back to 1928. It is dedicated to the study and conservation of wild birds looks after several areas, such as Beesands Ley. There is also the RSPB, which has reserves in the county, as well as English Nature, who look after several reserves such as Dawlish Warren.

The botany of the county is very diverse and includes some rare species not found elsewhere in the British Isles other than Cornwall. Botanical reports begin in the 17th century and there is a Flora Devoniensis by Jones and Kingston in 1829, and a Flora of Devon in 1939 by Keble Martin and Fraser.[6][7] There is a general account by W. P. Hiern and others in The Victoria History of the County of Devon, vol. 1 (1906); pp. 55–130, with map. Devon is divided into two Watsonian vice-counties: north and south, the boundary being an irregular line approximately across the higher part of Dartmoor and then along the canal eastwards.

Rising temperatures have led to Devon becoming the first place in modern Britain to cultivate olives commercially.[8]

History

Human occupation

Kents Cavern in Torquay had produced human remains from 30-40,000 years ago. Dartmoor is thought to have been occupied by Mesolithic hunter-gatherer peoples from about 6,000 BC. The Romans held the area under military occupation for around 350 years. Later, the area became a frontier between Welsh Dumnonia and English Wessex, and it was largely absorbed into Wessex by the mid 9th century. According to William of Malmesbury, the border with Cornwall was set by King Athelstan on the east bank of the River Tamar in 936, though historians doubt that Cornwall was absorbed so late; King Athelstan's grandfather King Alfred had several estates there.

Devon's seagoing tradition provided many of the heroes of the heroic age of the sea. Sir Francis Drake was born outside Tavistock and built his mansion not far off. The ships which fought the Spanish Armada sailed from Plymouth manned by men of Devon, as did all the great sea adventures.

Devon has also featured in most of the civil conflicts in England since the Norman Conquest, including the Wars of the Roses, Perkin Warbeck's rising in 1497, the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549, and the English Civil War. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 began with the landing of William of Orange at Brixham.

Devon has produced tin, copper and other metals from ancient times. Devon's tin miners enjoyed a substantial degree of independence through Devon's Stannary Parliament, which dates back to the 12th century. The last recorded sitting was in 1748.[9]

Economy and industry

Devon is disadvantaged economically compared to other parts of southern England, owing to the decline of a number of core industries, notably fishing, mining and farming. Consequently, most of Devon has qualified for the European Community Objective 2 status. Agriculture has been an important industry in Devon since the 19th century.[10] The 2001 foot and mouth crisis harmed the farming community severely.[11]

The attractive lifestyle of the area is drawing in new industries which are not heavily dependent upon geographical location; Dartmoor, for instance, has recently seen a significant rise in the percentage of its inhabitants involved in the financial services sector. In 2003, the Meteorological Office, the United Kingdom's national and international weather service, moved to Exeter. Devon is one of the rural counties, with the advantages and challenges characteristic of these. Despite this, the county's economy is also heavily influenced by its two main urban centres, Plymouth and Exeter.

Since the rise of seaside resorts with the arrival of the railways in the 19th century, Devon's economy has been heavily reliant on tourism. The county's economy has followed the declining trend of British seaside resorts since the mid-20th century, with some recent revival. This revival has been aided by the designation of much of Devon's countryside and coastline as the Dartmoor and Exmoor national parks, and the Jurassic Coast and Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Sites. In 2004 the county's tourist revenue was £1.2 billion.

Hundreds

Devon is divided into 32 hundreds:[12]

|

|

|

|

Towns and villages

The greatest towns of Devon are its two cities: Plymouth, a historic port and the largest town of the southwest, and Exeter, the county town. Torbay too has grown into a substantial conurbation centred on Torquay.

Devon's coast is lined with tourist resorts, many of which grew rapidly with the arrival of the railways in the 19th century. Examples include Dawlish, Exmouth and Sidmouth on the south coast, and Ilfracombe and Lynmouth on the north. The Torbay conurbation of Torquay, Paignton and Brixham on the south coast is perhaps the largest and most popular of these resorts.

Rural market towns in the county include Axminster, Barnstaple, Bideford, Honiton, Newton Abbot, Okehampton, Tavistock, Totnes and Tiverton.

Place names and customs

Devon's place names are a mixture of English and the British tongue (or Old Welsh) which was the speech of the land before the Anglo-Saxons came.

Many with the endings "coombe/combe" and "tor" – Coombe being the British word for "valley" or hollow (as the Welsh 'cwm') whilst "tor" derives from a number of Celtic loan-words in English (Old Welsh twrr and Gaelic tòrr) and is used as a name for the formations of rocks found on the moorlands. Its frequency is greatest in Devon, where it is the second most common place name component (after 'ton', derived from the Old English tun meaning enclosure, farmstead, farm or village).

River names, such as the Exe, Axe, Tavy, Tamar and Taw are from common British or earlier roots, while smaller local rivers have taken English names.

Westward Ho! has the distinction unique in Britain of having an exclamation mark in its name: its name derives from that of a novel.

Devon has a variety of festivals and traditional practices, including the traditional orchard-visiting Wassail in Whimple every 17 January and the carrying of flaming tar barrels in Ottery St Mary on 5 November each year, where people who have lived in Ottery for long enough are called upon to celebrate Bonfire Night by running through the village (and the gathered crowds) with flaming barrels of tar on their backs.[13] Berry Pomeroy still celebrates "Queen's Day" for Elizabeth I.

Food

The county has given its name to a number of culinary specialities. Food from the sea and food from the field are found in abundance.

The Devonshire cream tea, involving scones, jam and clotted cream, is thought to have originated in Devon (though claims have also been made for neighbouring counties); in other countries, such as Australia and New Zealand, it is known as a "Devonshire tea".[14][15][16]

Outside links

- BBC Devon

- Genuki Devon Historical, geographical and genealogical information

References

- ↑ |William Camden, Britannia.

- ↑ Edmonds, E. A., et al. (1975) South-West England; based on previous editions by H. Dewey (British Geological Survey UK Regional Geology Guide series no. 17, 4th ed.) London: HMSO ISBN 0-11-880713-7

- ↑ Edmonds, E. A.; McKeown, M. C.; Williams, M. (1975). "Carboniferous Rocks". South-West England. British Regional Geology. Dewey, H. (4th ed.). London: HMSO/British Geological Survey. p. 34. ISBN 0118807137.

- ↑ Dewey, Henry (1948) British Regional Geology: South West England, 2nd ed. London: H.M.S.O.

- ↑ http://www.exmoor-nationalpark.gov.uk/index/learning_about/moor_facts.htm%7CExmoor National Park, National Park Facts |accessdate=2009-05-10

- ↑ Jones, John Pike & Kingston, J. F. (1829) Flora Devoniensis. 2 pts, in 1 vol. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green

- ↑ Martin, W. Keble & Fraser, G. T. (eds.) (1939) Flora of Devon. Arbroath

- ↑ Paul Simons (2007-05-14). "Britain warms to the taste for home-grown olives". London: Times Online. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/weather/article1785059.ece. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ↑ "Devon's Mining History and Stannary parliament". users.senet.com.au. http://users.senet.com.au/~dewnans/Devon_Stannary_History.html. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- ↑ [1], South West Chamber of Rural Enterprise

- ↑ In Devon, the county council estimated that 1,200 jobs would be lost in agriculture and ancillary rural industries — Hansard, 25th April 2001

- ↑ GENUKI http://genuki.cs.ncl.ac.uk/DEV/Hundreds.html

- ↑ "Ottery Tar Barrels". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/devon/discovering/legends/ottery_tar_barrels.shtml. Retrieved 2008-05-14.

- ↑ Mason, Laura; Brown, Catherine (1999) From Bath Chaps to Bara Brith. Totnes: Prospect Books

- ↑ Pettigrew, Jane (2004) Afternoon Tea. Andover: Jarrold

- ↑ Fitzgibbon, Theodora (1972) A Taste of England: the West Country. London: J. M. Dent

Further reading

- Oliver, George (1846) Monasticon Dioecesis Exoniensis: being a collection of records and instruments illustrating the ancient conventual, collegiate, and eleemosynary foundations, in the Counties of Cornwall and Devon, with historical notices, and a supplement, comprising a list of the dedications of churches in the Diocese, an amended edition of the taxation of Pope Nicholas, and an abstract of the Chantry Rolls [with supplement and index]. Exeter: P. A. Hannaford, 1846, 1854, 1889

- Pevsner, N. (1952) North Devon and South Devon (Buildings of England). 2 vols. Penguin Books

- Stabb, John Some Old Devon Churches: their rood screens, pulpits, fonts, etc.. 3 vols. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent, 1908, 1911, 1916

| Counties of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

Aberdeen • Anglesey • Angus • Antrim • Argyll • Armagh • Ayr • Banff • Bedford • Berks • Berwick • Brecknock • Buckingham • Bute • Caernarfon • Caithness • Cambridge • Cardigan • Carmarthen • Chester • Clackmannan • Cornwall • Cromarty • Cumberland • Denbigh • Derby • Devon • Dorset • Down • Dumfries • Dunbarton • Durham • East Lothian • Essex • Fermanagh • Fife • Flint • Glamorgan • Gloucester • Hants • Hereford • Hertford • Huntingdon • Inverness • Kent • Kincardine • Kinross • Kirkcudbright • Lanark • Lancaster • Leicester • Lincoln • Londonderry • Merioneth • Middlesex • Midlothian • Monmouth • Montgomery • Moray • Nairn • Norfolk • Northampton • Northumberland • Nottingham • Orkney • Oxford • Peebles • Pembroke • Perth • Radnor • Renfrew • Ross • Roxburgh • Rutland • Selkirk • Shetland • Salop • Somerset • Stafford • Stirling • Suffolk • Surrey • Sussex • Sutherland • Tyrone • Warwick • West Lothian • Westmorland • Wigtown • Wilts • Worcester • York |