Norwich: Difference between revisions

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

|latitude=52.62834 | |latitude=52.62834 | ||

|longitude=1.29656 | |longitude=1.29656 | ||

|post town=Norwich | |||

|postcode=NR1–NR16 | |postcode=NR1–NR16 | ||

|dialling code=01603 | |dialling code=01603 | ||

| Line 26: | Line 27: | ||

==Norwich Cathedral== | ==Norwich Cathedral== | ||

[[File:Norwich Cathedral from lawns.jpg|left|thumb|180px|Northwich Cathedral]] | [[File:Norwich Cathedral from lawns.jpg|left|thumb|180px|Northwich Cathedral]] | ||

'''Norwich Cathedral''', | {{Main|Norwich Cathedral}} | ||

'''Norwich Cathedral''', the '''Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity''' is a cathedral of the [[Church of England]] and the seat of the [[Diocese of Norwich]]. | |||

It has the highest spire | It has the highest spire in Britain after [[Salisbury Cathedral|Salisbury]]. The total length of the building is 461 feet. | ||

The cathedral was started in 1096 by Bishop Herbert de Losinga and constructed out of flint and mortar and faced with a cream coloured Caen limestone. A Saxon settlement and two churches were demolished to make room for the buildings. The building was finished in 1145 and had the fine Norman tower, that we see today, topped with a wooden spire covered with lead. Several periods of damage caused rebuilding to the nave and spire but after many years the building was much as we see it now, from the final erection of the stone spire in 1480. | The cathedral was started in 1096 by Bishop Herbert de Losinga and constructed out of flint and mortar and faced with a cream-coloured Caen limestone. A Saxon settlement and two churches were demolished to make room for the buildings. The building was finished in 1145 and had the fine Norman tower, that we see today, topped with a wooden spire covered with lead. Several periods of damage caused rebuilding to the nave and spire but after many years the building was much as we see it now, from the final erection of the stone spire in 1480. | ||

The large cloister has over | The large cloister has over a thousand bosses including several hundred carved and ornately painted ones. The buildings are on the lowest part of the plain of the River Wensum n Norwich and surrounded on three sides by hills and an area of scrubland, Mousehold heath. The Cathedral can be seen from just about any location in the city. | ||

===Structure=== | ===Structure=== | ||

| Line 57: | Line 59: | ||

The Angles settled on the site of the modern city from around the 5th – 7th centuries<ref name=NAUDA1>{{cite book|title=An Archaeological Evaluation at 17–27 Fishergate, Norwich, Norfolk|year=2005|publisher=NORFOLK ARCHAEOLOGICAL UNIT|location=17–27 Fishergate, Norwich|url=http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/oasis_reports/norfolka1/ahds/dissemination/pdf/norfolka1-15734_1.pdf|author=David Adams|edition=HER 41303N|accessdate=26 January 2011|page=11|format=PDF|month=June}}</ref> founding the towns of Norþwic (from which Norwich gets its name), Westwic (at Norwich-over-the-Water) and the secondary settlement at Thorpe. | The Angles settled on the site of the modern city from around the 5th – 7th centuries<ref name=NAUDA1>{{cite book|title=An Archaeological Evaluation at 17–27 Fishergate, Norwich, Norfolk|year=2005|publisher=NORFOLK ARCHAEOLOGICAL UNIT|location=17–27 Fishergate, Norwich|url=http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/oasis_reports/norfolka1/ahds/dissemination/pdf/norfolka1-15734_1.pdf|author=David Adams|edition=HER 41303N|accessdate=26 January 2011|page=11|format=PDF|month=June}}</ref> founding the towns of Norþwic (from which Norwich gets its name), Westwic (at Norwich-over-the-Water) and the secondary settlement at Thorpe. | ||

There are two suggested models of development for Norwich. It is possible that three separate early Anglo-Saxon settlements, one on the north of the river and two either side on the south, joined together as they grew or that one Anglo-Saxon settlement, on the north of the river, emerged in the mid-7th century after the abandonment of the previous three. The ancient city was a thriving centre for trade and commerce in East Anglia in 1004 | There are two suggested models of development for Norwich. It is possible that three separate early Anglo-Saxon settlements, one on the north of the river and two either side on the south, joined together as they grew or that one Anglo-Saxon settlement, on the north of the river, emerged in the mid-7th century after the abandonment of the previous three. The ancient city was a thriving centre for trade and commerce in East Anglia in AD 1004 when it was raided and burnt by Swein Forkbeard the Viking. Mercian coins and shards of pottery from the Rhineland dating to the 8th century suggest that long distance trade was happening long before this. Between 924 and 939, Norwich became fully established as a town, in witness of which it had its own royal mint. The word ''Norvic'' appears on coins across Europe minted during this period, in the reign of King Athelstan. | ||

The Danes were a strong cultural influence in Norwich for 40 to 50 years at the end of the 9th century, setting an Anglo-Scandinavian district up towards the north end of present-day King Street. | The Danes were a strong cultural influence in Norwich for 40 to 50 years at the end of the 9th century, setting an Anglo-Scandinavian district up towards the north end of present-day King Street. | ||

| Line 167: | Line 169: | ||

==Great buildings of the city== | ==Great buildings of the city== | ||

Norwich has a wealth of historical architecture. The mediæval period is represented by the 11th century Norwich Cathedral, 12th century castle (now a museum) and a large number of parish churches. During the Middle Ages, 57 churches stood within the city wall; 31 still exist today.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.historicalnorwich.co.uk/churches.htm | title=Old Norwich – Churches | work=Historical Norwich | accessdate=8 March 2006}}</ref> This gave rise to the common regional saying that it had a church for every week of the year, and a pub for every day. Most of the mediæval buildings are in the city centre. Notable examples of secular mediæval architecture are Dragon Hall, built in about 1430, and The Guildhall, built 1407–1413, with later additions. From the 18th century the pre-eminent local name is Thomas Ivory, who built the Assembly Rooms (1776), the Octagon Chapel (1756), St Helen's House (1752) in the grounds of the Great Hospital, and innovative speculative housing in Surrey Street (c. 1761). Ivory should not be confused with the Irish architect of the same name and similar period. | Norwich has a wealth of historical architecture. The mediæval period is represented by the 11th-century Norwich Cathedral, 12th-century castle (now a museum) and a large number of parish churches. During the Middle Ages, 57 churches stood within the city wall; 31 still exist today.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.historicalnorwich.co.uk/churches.htm | title=Old Norwich – Churches | work=Historical Norwich | accessdate=8 March 2006}}</ref> This gave rise to the common regional saying that it had a church for every week of the year, and a pub for every day. Most of the mediæval buildings are in the city centre. Notable examples of secular mediæval architecture are Dragon Hall, built in about 1430, and The Guildhall, built 1407–1413, with later additions. From the 18th century the pre-eminent local name is Thomas Ivory, who built the Assembly Rooms (1776), the Octagon Chapel (1756), St Helen's House (1752) in the grounds of the Great Hospital, and innovative speculative housing in Surrey Street (c. 1761). Ivory should not be confused with the Irish architect of the same name and similar period. | ||

The 19th century saw much growth in the city. The local architect of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, George Skipper (1856–1948), built Norwich Union on Surrey Street, the Art Nouveau Royal Arcade; and the Hotel de Paris in the nearby seaside town of [[Cromer]]. | The 19th century saw much growth in the city. The local architect of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, George Skipper (1856–1948), built Norwich Union on Surrey Street, the Art Nouveau Royal Arcade; and the Hotel de Paris in the nearby seaside town of [[Cromer]]. | ||

Latest revision as of 19:05, 9 December 2024

| Norwich | |

| Norfolk | |

|---|---|

The Lower Close and Norwich Cathedral | |

| Location | |

| Grid reference: | TG233087 |

| Location: | 52°37’42"N, 1°17’48"E |

| Data | |

| Population: | 259,100 |

| Post town: | Norwich |

| Postcode: | NR1–NR16 |

| Dialling code: | 01603 |

| Local Government | |

| Council: | Norwich |

Norwich is a city in the heart of Norfolk, of which it is the only city and the county town. During the 11th century, Norwich was the largest city in England after London, and one of the most important places in the kingdom.

The city stands on the banks of the River Wensum, a broad river which soon after leaving the city joins the River Yare and enters the Norfolk Broads, all at sea level. Norwich is thus at the edge of those flat lands for which Norfolk is rightly famous and the rivers, tidal into the city itself, have for endless ages provided a route for the Norwich merchants to the coast and thus to the world.

The best way to confuse a visitor in Norwich is to tell them to turn left at the church, because the city has so many they appear to stand at every corner. Norwich today has more mediæval churches than any other city in Western Europe north of the Alps. A large portion of the city's heart is taken up with the precincts of the Cathedral: the Cathedral itself, its soaring tower second only to Salisbury, stands facing the most ancient part of Norwich, Tombland, and behind it are the gardens, fields and chapels belonging to the Bishop.

The Mediæval streets

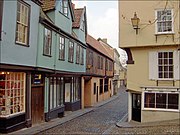

While the passing motorist, locked to his car, may rush through and see the modern roads and think the city a very pretty, somewhat eccentric but essentially expected town, the one who steps out and explores the town on foot has delights awaiting him.

The heart of Norwich is not in the modernised shopping streets but in the tangled, ancient streets and ways behind the through-roads; Norwich is the most complete mediaeval town in Britain. these little streets are a jumble of building from every age; the Middle Ages, the Tudor, the Georgian and indeed modern, all creating together a town which charms all visitors who care to look.

Norwich Cathedral

- Main article: Norwich Cathedral

Norwich Cathedral, the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity is a cathedral of the Church of England and the seat of the Diocese of Norwich.

It has the highest spire in Britain after Salisbury. The total length of the building is 461 feet.

The cathedral was started in 1096 by Bishop Herbert de Losinga and constructed out of flint and mortar and faced with a cream-coloured Caen limestone. A Saxon settlement and two churches were demolished to make room for the buildings. The building was finished in 1145 and had the fine Norman tower, that we see today, topped with a wooden spire covered with lead. Several periods of damage caused rebuilding to the nave and spire but after many years the building was much as we see it now, from the final erection of the stone spire in 1480.

The large cloister has over a thousand bosses including several hundred carved and ornately painted ones. The buildings are on the lowest part of the plain of the River Wensum n Norwich and surrounded on three sides by hills and an area of scrubland, Mousehold heath. The Cathedral can be seen from just about any location in the city.

Structure

The structure of the cathedral is primarily in the Norman style and retains the greater part of its original stone structure. Building started in 1096 and the cathedral was completed in 1145. It was built from flint and mortar and faced with cream coloured Caen limestone.[1] A pre-Norman village and two churches were demolished to make room for the buildings and a canal cut to allow access for the boats bringing the stone and building materials which were taken up the Wensum and unloaded at Pulls Ferry, Norwich.[1] It was damaged after riots in 1270, rebuilt by 1278 and re–consecrated by Edward I. It has the finest Norman tower in England and the highest after Salisbury. The original spire was wooden and sheathed in lead but was blown down by a storm in 1362.[1]

A large cloister with over 1,000 bosses was started in 1297 and finally finished in 1430 after the Black Death. The building was vaulted between 1416 and 1472 in a spectacular manner with hundreds of ornately carved, painted and gilded bosses. In 1463 the spire was struck by lightning and caused a fire to rage through the nave which was so intense it turned some of the Caen stone pink.[1] In 1480 the Bishop of Norwich, James Goldwell, ordered the building of the stone spire which is still in place today, with flying buttresses later added to help support the roofs.

Precincts

The precinct of the cathedral, the limit of the former monastery, is between Tombland (the Anglo-Saxon market place) and the River Wensum and the Cathedral Close, which runs from Tombland into the cathedral grounds, contains a number of interesting buildings from the 15th through to the 19th century including the remains of the infirmary.

The grounds also house the King Edward VI school, statues to the Duke of Wellington and Admiral Nelson and the grave of Edith Cavell.

17th century: decline and restoration

The Cathedral was partially in ruins when John Cosin was there at Grammar School in the early 17th century, and the former bishop was an absentee figure. During the reign of King Charles I, an angry Puritan mob invaded the cathedral and destroyed all Romish symbols in 1643. The building, abandoned the following year, lay in ruins for two decades. Norwich Bishop Joseph Hall provides a graphic description from his book Hard Measure:

It is tragical to relate the furious sacrilege committed under the authority of Linsey, Tofts the sheriff, and Greenwood: what clattering of glasses, what beating down of walls, what tearing down of monuments, what pulling down of seats, and wresting out of irons and brass from the windows and graves; what defacing of arms, what demolishing of curious stone-work, that had not any representation in the world but of the cost of the founder and skill of the mason; what piping on the destroyed organ-pipes; vestments, both copes and surplices, together with the leaden cross which had been newly sawed down from over the greenyard pulpit, and the singing-books and service-books, were carried to the fire in the public market-place; a lewd wretch walking before the train in his cope trailing in the dirt, with a service-book in his hand, imitating in an impious scorn the tune, and usurping the words of the litany. The ordnance being discharged on the guild-day, the cathedral was filled with musketeers, drinking and tobacconing as freely as if it had turned ale-house.

After the Restoration in 1660, King Charles II began the restoration of the Cathedral.

History

Foundation

The Angles settled on the site of the modern city from around the 5th – 7th centuries[2] founding the towns of Norþwic (from which Norwich gets its name), Westwic (at Norwich-over-the-Water) and the secondary settlement at Thorpe.

There are two suggested models of development for Norwich. It is possible that three separate early Anglo-Saxon settlements, one on the north of the river and two either side on the south, joined together as they grew or that one Anglo-Saxon settlement, on the north of the river, emerged in the mid-7th century after the abandonment of the previous three. The ancient city was a thriving centre for trade and commerce in East Anglia in AD 1004 when it was raided and burnt by Swein Forkbeard the Viking. Mercian coins and shards of pottery from the Rhineland dating to the 8th century suggest that long distance trade was happening long before this. Between 924 and 939, Norwich became fully established as a town, in witness of which it had its own royal mint. The word Norvic appears on coins across Europe minted during this period, in the reign of King Athelstan.

The Danes were a strong cultural influence in Norwich for 40 to 50 years at the end of the 9th century, setting an Anglo-Scandinavian district up towards the north end of present-day King Street.

Middle Ages

At the time of the Norman Conquest the city was one of the largest in England. The Domesday Book states that it had approximately twenty-five churches and a population of between five and ten thousand. It also records the site of an Anglo-Saxon church in Tombland, the site of the Saxon market place and the later Norman cathedral. Norwich continued to be a major centre for trade, the River Wensum being a convenient export route to the River Yare and Great Yarmouth, which served as the port for Norwich. Quern stones, and other artefacts from Scandinavia and the Rhineland have been found during excavations in Norwich city centre which date from the 11th century onwards.

Norwich Castle was founded soon after the Norman Conquest.[3] The Domesday Book records that 98 Saxon homes were demolished to make way for the castle.[4] The Normans established a new focus of settlement around the Castle and the area to the west of it: this became known as the "New" or "French" borough, centred on the Normans' own market place which survives to the present day as Norwich Market.

In 1096, Herbert de Losinga, the Bishop of Thetford, began construction of Norwich Cathedral. The chief building material for the Cathedral was limestone, imported from Caen in Normandy. To transport the building stone to the cathedral site, a canal was cut from the river (from the site of present-day Pulls Ferry), all the way up to the east wall. Herbert de Losinga then moved his See]] there to what became the cathedral church for the Diocese of Norwich. The bishop of Norwich still signs himself Norvic.

Norwich received a royal charter from Henry II in 1158, and another one from Richard I in 1194. The castle keep was built in the same century.

The massacre of 1190

In 1144, the Jews of Norwich were accused of ritual murder after a boy (William of Norwich) was found dead with stab wounds. This was the first incidence of blood libel against Jews in England. The story was turned into a cult, William acquire the status of martyr and was subsequently canonised. The cult of St William attracted large numbers of pilgrims, bringing wealth to the local church. On 6 February 1190, all the Jews of Norwich were massacred except for a few who found refuge in the castle.

At the site of a mediæval well, the bones of 17 individuals, including 11 children, were found in 2004 by workers preparing the ground for construction of a Norwich shopping centre. The remains were determined by forensic scientists to most probably be the remains of Jews murdered in the 12th century, and a DNA expert determined that the victims were all related, most probably coming from one Ashkenazi Jewish family.[5] The study of these remains was featured in an episode of the BBC Television documentary series History Cold Case.[6]

Wool

The engine of trade was wool from Norfolk's sheepwalks. Wool made England rich, and the port of Norwich "in her state doth stand With towns of high'st regard the fourth of all the land", as Michael Drayton noted in Poly-Olbion (1612). The wealth generated by the wool trade throughout the Middle Ages financed the construction of many fine churches; consequently, Norwich still has more mediæval churches than any other city in Western Europe north of the Alps. Throughout this period Norwich established wide-ranging trading links with other parts of Europe, its markets stretching from Scandinavia to Spain and the city housing a Hanseatic warehouse. To organise and control its export to the Low Countries, Great Yarmouth, as the port for Norwich, was designated one of the staple ports under terms of the 1353 Statute of the Staple.

By the middle of the 14th century the city walls, about two and a half miles long, had been completed. These, along with the river, enclosed a larger area than that of the City of London. However, when the city walls were constructed it was made illegal to build outside them, inhibiting expansion of the city.

Around this time, the city was made a county corporate and Norfolk, of which it was and is the county town, became one of the most densely populated and prosperous counties of Britain.

Early Modern Period (1485–1640)

Hand-in-hand with the wool industry, this key religious centre experienced a Reformation significantly different to other parts of England. Muriel McClendon describes a Tudor Norwich whose magistracy unusually found ways of managing religious discord whilst maintaining civic harmony.[7]

The year 1549 saw an urban rebellion against the papist Queen, Mary I. For several weeks, Kett's rebels took control of Norwich; it divided a city and appears to have linked Protestantism with the plight of the urban poor but was underscored by the arrival of Flemish 'Strangers' fleeing Papist persecution and who eventually numbering as many as a third of the city's population; now in daner of persecution in England.[8]

The great 'Stranger' immigration of 1567 brought a substantial Flemish and Walloon community of Protestant weavers to Norwich, where they are said to have been made welcome.[9] Norwich has traditionally been the home of various dissident minorities, notably the French Huguenots and the Walloons from the Low Countries in the 16th and 17th centuries. The merchant's house—now a museum—which was their earliest base in the city is still known as 'Strangers' Hall'. It seems that the Strangers were integrated into the local community without a great deal of animosity, at least among the business fraternity who had the most to gain from their skills. The arrival of the Strangers in Norwich bolstered trade with mainland Europe, fostering a movement toward religious reform and radical politics in the city.

The Norwich canary was first introduced into England by Flemish refugees fleeing from Spanish persecution in the 16th century. They brought with them not only advanced techniques in textile working but also their pet canaries, which they began to breed locally, the little yellow bird eventually to become, in the 20th century, the city's most beloved mascot. The canary is the emblem of the city's football club, Norwich City FC, nicknamed "The Canaries".

Printing was introduced to the city by Anthony de Solempne, one of the 'Strangers' in 1567 but did not become established and had died out by about 1572.[10]

English Civil Wars and dissentions

Across the Eastern Counties Cromwell's powerful Eastern Association was eventually dominant. However, to begin with, there had been a large element of Royalist sympathy within Norwich, which remained throughout the civil-war period. The Bishop, Matthew Wrenn, was a forceful supporter of Charles I but Parliamentary successfully recruited here and the Royalist party was stifled by a lack of commitment from the aldermen, and isolation from Royalist-held regions.[11] In 1648, Parliamentary forces tried to quell a Royalist riot. The latter's gunpowder was set off by accident in the city centre, causing mayhem: the events were nown as 'The Great Blow'. (Hopper says that the explosion 'ranks among the largest of the century'.) Stoutly defended though East Anglia was by the parliamentary army, there are said to have been pubs in Norwich where the King's health was still drunk and the name of the Protector sung to ribald verse.

The Restoration of 1660 opened a century of great prosperity for the cloth industry, comparable only to those of the West Country and Yorkshire.[12] But unlike other cloth-manufacturing regions, Norwich weaving brought greater urbanisation; being substantially concentrated in the surrounds of the city itself, creating an urban society, with features such as leisure time, alehouses, and other public fora which provided opportunities for debate and argument.[13]

Factions and the seventeenth century

Writing of the early 18th century, Pound describes the city's rich cultural life, the winter-theatre season, the festivities accompanying the summer assizes, and other popular entertainments. Norwich was the wealthiest town in England with a sophisticated poor-relief system, and a large influx of foreign refugees.[14] Despite having suffered severe episodes of plague, the city had a population of almost 30,000. Whilst this made Norwich unique in England it placed her in the company of about fifty cities in Europe. In some, like Lyon or Dresden, this was, as in the case of Norwich, linked to an important proto-industry, such as textiles or china pottery; in some, such as Vienna, Madrid or Dublin,to the city's status as an administrative capital; in others such as Antwerp, Marseilles or Cologne to its positioning on an important trade route of sea or river.[15]

However Norwich of the late-17th century was as ever riven politically. Humphrey Prideaux, dean of the cathedral in 1681, described 'two factions, Whig and Tory...and both contend for their way with the utmost violence'.[16] After the 1688 Glorious Revolution, the Bishop, William Lloyd, was a "non-juror", refusing to take the oaths of allegiance to the new monarchs. One report has it that in 1704 the landlord of Fowler's alehouse 'with a glass of beer in hand, went down on his knees and drank a health to James the third, wishing the Crowne well and settled on his head'[17] 'Never was a city in the miserable kingdom so wretchedly divided as this' said the London Post.[18]

In 1716, the year after the Jacobite rebellion had been defeated it is reported that at a play at the New Inn, the Pretender was cheered and the audience booed and hissed every time King George's name was mentioned, while in 1722 supporters of the king were said to be 'hiss'd at and curst as they go in the streets', and in 1731 'a Tory mobb, in a great body, went through several parts of this city, in a riotous manner, cursing and abusing such as they knew to be friends of the government'.[19] But the Whigs gradually gained control and by the 1720s ensured that all adult males working in the textile industry could become burgesses, ensuring Whig dominance of the Corporation, but also polarisation. Jacobitism survived until the defeat of the '45 Rebellion.

Britain's first provincial newspaper, the Norwich Post was published in 1701 and by 1726 there were rival Whig and Tory presses. The Theatre Royal had opened in 1758. In 1750 Norwich had nine booksellers and after 1780 a 'growing number of circulating and subscription libraries'.[20] Metropolitan culture thrived. Freemen of the city had the right to trade but to vote at elections, and they numbered about 2,000 in 1690, rising to over 3,300 by the mid-1730s; their numbers did at one point reach one third of the adult male population.[21] Apart from London, Norwich was probably still the largest of those boroughs which were democratically governed.[22]

In the late-18th century, Norwich intellectual life flourished. The city 'boasted of her intellectual supper-parties, where, amidst a pedantry which would now make laughter hold both his sides, there was much that was pleasant and salutary: and finally she called herself The Athens of England.[23]

Notwithstanding Norwich's hitherto industrial prosperity, by the 1790s the wool trade was experiencing intense competition. It came from both Yorkshire woollens, and increasingly from Lancashire cottons. The effects were aggravated by the loss of continental markets after Britain went to war with revolutionary France in 1793. The end of Norwich's pre-eminence was beginning.

In 1797 Thomas Bignold, a 36-year-old wine merchant and banker, founded the first Norwich Union Society. Some years earlier, when he moved from Kent to Norwich, Bignold had been unable to find anyone willing to insure him against the threat from highwaymen. With the entrepreneurial thought that nothing was impossible, and aware that in a city built largely of wood the threat of fire was uppermost in people's minds, Bignold formed the "Norwich Union Society for the Insurance of Houses, Stock and Merchandise from Fire". The new business, which became known as the Norwich Union Fire Insurance Office, was a "mutual" enterprise. Norwich Union was later to become the country's largest insurance giant and remains a major employer in Norwich, though now under the bland, foreign name of "Aviva".

From earliest times, Norwich was a centre of textile manufacture. Towards the end of the 18th century, in the 1780s, the manufacture of Norwich shawls became an important industry[24] and remained so for nearly one hundred years. The shawls were a high-quality fashion product and rivalled those made in other towns such as Paisley (which entered shawl manufacture in about 1805, some 20 or more years after Norwich). With changes in women's fashion in the later Victorian period, the popularity of shawls declined and eventually manufacture ceased. Examples of Norwich shawls are now highly sought after by collectors of textiles.[25]

From 1808 to 1814 Norwich hosted a station in the shutter telegraph chain which connected the Admiralty in London to its naval ships in the port of Great Yarmouth.

The Victorian Age

Until the Industrial Revolution, as the capital of England's most populous and prosperous county, Norwich vied with Bristol as England's second city. As the industrial towns grew, however, Norwich, isolated from the industrial heartlands and without the coal which fuelled the revolution, was surpassed by the young towns of the north and midlands.

Norwich's geographical isolation was such that until 1845 when a railway connection was established, it was often quicker to travel to Amsterdam by boat than to London. The railway was introduced to Norwich by Morton Peto, who also built the line to Great Yarmouth.

20th century

In the early part of the 20th century Norwich still had several major manufacturing industries. Among these were the manufacture of shoes, clothing, joinery, and structural engineering as well as aircraft design and manufacture. Important employers included Boulton & Paul, Barnards (inventors of machine produced wire netting), and electrical engineers Laurence Scott and Electromotors.

Norwich also has a long association with chocolate manufacture, primarily through the local firm of Caley's, which began as a manufacturer and bottler of mineral water and later diversified into making chocolate and Christmas crackers.

Norwich suffered extensive bomb damage during Second World War, affecting large parts of the old city centre and Victorian terrace housing around the centre. Industry and the rail infrastructure also suffered. The heaviest raids occurred on the nights of 27/28th and 29/30 April 1942; as part of the Baedeker raids.

HMSO, once the official publishing and stationery arm of the British government and one of the largest print buyers, printers and suppliers of office equipment in the United Kingdom, moved most of its operations from London to Norwich in the 1970s.

The city was home to a long-established tradition of brewing,[26] and several large breweries continued in business into the second half of the century. The main brewers were Morgans, Steward and Patteson, Youngs Crawshay and Youngs, Bullard and Son, and the Norwich Brewery. By the 1970s, only the Norwich remained, and that closed in 1985.

Museums

Norwich has a number of important museums which reflect both the rich history of the City and of Norfolk, as well as wider interests.

- Norwich Castle Museum, with extensive collections of archaeological finds from Norfolk, art (including a fine collection of paintings by the Norwich School, ceramics (including the largest collection of British teapots), silver, and Natural History.[27]

- Bridewell Museum (closed since 2010 for redevelopment until Summer 2012. It had exhibits connected with the historic industries of Norwich: weaving, shoe-making, iron foundries, engineering, milling, brewing, chocolate-making and food.

- Strangers' Hall, one of the oldest buildings in Norwich: a merchant's house dating to the early 14th century.[28]

- Royal Norfolk Regimental Museum in the old Shirehall, close to the Castle, soon to move to Norwich Castle Museum

- City of Norwich Aviation Museum at Horsham St Faith[29]

- John Jarrold Printing Museum, at Whitefriars[30]

- Dragon Hall, in King Street; a fine example of a mediæval merchants' trading hall, mostly dating from about 1430 and unique in Western Europe.

- Costume and Textiles Study Centre[31]

Theatres

Norwich has several theatres, seating anything from 100 to 1,300.

- Theatre Royal, on its present site for nearly 250 years, is the largest in the city.

- Norwich Playhouse in the heart of the city

- Maddermarket Theatre opened in 1921: the first permanent recreation of an Elizabethan Theatre.

- Norwich Puppet Theatre, founded in 1979

- The Garage, a studio theatre

- CCN Drama Centre in the grounds of City College Norwich (CCN)

- Sewell Barn Theatre; the smallest theatre in Norwich seating just 100

- Norwich Arts Centre, opened in 1977 in St. Benedict's Street

Parks, gardens and open spaces

Chapelfield Gardens in central Norwich became the city's first public park in November 1880. From the start of the 20th century Norwich Corporation began buying and leasing land to develop parks when funds became available. Sewell Park and James Stuart Gardens are examples of land donated by benefactors. After First World War, a new series of formal parks was laid out as a way to alleviate unemployment: Heigham Park (1924), Wensum Park (1925), Eaton Park (1928), Waterloo Park (1933).

Currently (2011), the city has 23 parks, 95 open spaces and 59 natural areas managed by the council.[32]

Great buildings of the city

Norwich has a wealth of historical architecture. The mediæval period is represented by the 11th-century Norwich Cathedral, 12th-century castle (now a museum) and a large number of parish churches. During the Middle Ages, 57 churches stood within the city wall; 31 still exist today.[33] This gave rise to the common regional saying that it had a church for every week of the year, and a pub for every day. Most of the mediæval buildings are in the city centre. Notable examples of secular mediæval architecture are Dragon Hall, built in about 1430, and The Guildhall, built 1407–1413, with later additions. From the 18th century the pre-eminent local name is Thomas Ivory, who built the Assembly Rooms (1776), the Octagon Chapel (1756), St Helen's House (1752) in the grounds of the Great Hospital, and innovative speculative housing in Surrey Street (c. 1761). Ivory should not be confused with the Irish architect of the same name and similar period.

The 19th century saw much growth in the city. The local architect of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, George Skipper (1856–1948), built Norwich Union on Surrey Street, the Art Nouveau Royal Arcade; and the Hotel de Paris in the nearby seaside town of Cromer.

-

Northwich Cathedral Spire

-

Elm Hill, an intact mediæval street

-

20 Old Westlegate and All Saints' Church

-

Cow Tower on the banks of the River Wensum

-

Gentleman's Walk

Media

Norwich is the headquarters of BBC East, the BBC's presence in the east of England, and BBC Radio Norfolk, BBC Look East, Inside Out and The Politics Show are all broadcast from the BBC studios in the The Forum in the city centre.

ITV Anglia, formerly Anglia Television, is based in Norwich.

Sights about the city

Norwich is a popular destination for a city break. As part of ambitious aims to promote Norwich's heritage internationally, Norwich 12 has been launched - a collection of listed buildings in Norwich. The group consists of:

Norwich Castle

Norwich Cathedral

- The Great Hospital

- The Halls: St Andrew's and Blackfriars'

- The Guildhall

- Dragon Hall

- The Assembly House

- St James Mill

- St John the Baptist Roman Catholic Cathedral

- Surrey House

- City Hall

- The Forum

Other fine sights about Norwich are:

- The cobbled streets and museums of old Norwich

- Norwich Market: one of the largest outdoor markets in England

- Cow Tower

- Colman's Mustard Shop

Outside links

| ("Wikimedia Commons" has material about Norwich) |

- Norwich Cathedral Official site

- A history of the choristers of Norwich Cathedral

- Norwich Literary History

- Flickr images tagged Norwich Cathedral

- Norwich City Council

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Timeline of Norwich Cathedral". Norwich Cathedral. http://www.cathedral.org.uk/historyheritage/timeline-timeline.aspx. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ David Adams (June 2005) (PDF). An Archaeological Evaluation at 17–27 Fishergate, Norwich, Norfolk (HER 41303N ed.). 17–27 Fishergate, Norwich: NORFOLK ARCHAEOLOGICAL UNIT. p. 11. http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/oasis_reports/norfolka1/ahds/dissemination/pdf/norfolka1-15734_1.pdf. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- ↑ "Norwich Castle". Pastscape. English Heritage. http://www.pastscape.org.uk/hob.aspx?hob_id=132268. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ↑ Harfield, C. (1991) "A Hand-list of Castles Recorded in the Domesday Book" English Historical Review, pp. 373, 384

- ↑ "Jewish bones found in mediæval well in England". JTA. 27 June 2011. http://www.jta.org/news/article/2011/06/27/3088324/jewish-bones-found-in-mediæval-well-in-england. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ↑ "The Bodies in the Well". History Cold Case. BBC HD. 28 June 2011. No. 3, series 2.

- ↑ McClendon, M. The Quiet Reformation: Magistrates and the Emergence of Protestantism in Tudor Norwich (Stanford, 1999)

- ↑ Houlbroke, Ralph and McClendon, Muriel 'The Reformation' in Rawcliffe C and Wilson R (eds) 'Mediæval Norwich' (London 2004) p.257.

- ↑ R.W. Ketton-Cremer, "The Coming of the Strangers", in Norfolk Assembly1957:-30.

- ↑ Stoker, David (1981). Anthony de Solempne: attributions to his press. 6th series 3. London: The Bibliographical Society. 17–32..

- ↑ Hopper, A. "The Civil Wars" in Rawcliffe & Wilson (eds), "Norwich since 1550" (London 2004) pp.89–93

- ↑ Wilson, Richard 'Introduction' in Rawcliffe & Wilson (eds) "Norwich Since 1550" (London 2004) pp.xxv-xxvi.

- ↑ Wilson, Richard 'The Textile Industry' in Rawcliffe & Wilson (eds) "Norwich Since 1550" (London 2004) p.228

- ↑ Pound, 'Government to 1660' in Rawcliffe & Wilson (eds)" Norwich Since 1550" (London 2004), p.61

- ↑ For table of city sizes see Corfield P., 'From Second City to Regional Capital' in Rawcliffe & Wilson, (eds)" Norwich Since 1550" (London 2004) p143.

- ↑ Knights, Mark 'Politics 1660–1835' in Rawcliffe & Wilson. (eds) " Norwich since 1550" (London 2004)

- ↑ Quoted by Knights, M. 'Politics 1660–1835' qv. p.172

- ↑ Knights, M qv.

- ↑ Reports quoted by Knights, M. 'Politics 1660–1835' (qv), p.167.

- ↑ Dain, Angela. 'An Enlightened and Polite Society' in Rawcliffe & Wilson (eds) "Norwich Since 1550" (London 2004) pp. 194–5

- ↑ Knights, M. 'Politics 1660–1835' (qv) pp.168–9

- ↑ Jewson, C. 'The Jacobin City – a Portrait of Norwich in its Reaction to the French Revolution: 1788–1802' (London 1975)

- ↑ Martineau, Harriet 'Biographical Sketches 1852–1868' (1870)

- ↑ Norfolk Museums & Archaeology Service website—"Norwich Shawls"

- ↑ Norwich Textile website—"The Norwich Shawl Story"

- ↑ Norfolk Museums & Archaeology Service website—"Brewing in Norwich"

- ↑ Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service website – Norwich Castle Museum and Art Gallery

- ↑ Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service website – Strangers' Hall

- ↑ City of Norwich Aviation Museum website – Aviation Museum

- ↑ John Jarrold Printing Museum website – John Jarrold Printing Museum

- ↑ Norwich Textiles website—Costumes and Textiles Study Centre

- ↑ Norwich parks Retrieved 1 July 2011

- ↑ "Old Norwich – Churches". Historical Norwich. http://www.historicalnorwich.co.uk/churches.htm. Retrieved 8 March 2006.

| Cities in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

Aberdeen • Armagh • Bangor (Caernarfonshire) • Bangor (County Down) • Bath • Belfast • Birmingham • Bradford • Brighton and Hove • Bristol • Cambridge • Canterbury • Cardiff • Carlisle • Chelmsford • Chester • Chichester • Colchester • Coventry • Derby • Doncaster • Dundee • Dunfermline • Durham • Ely • Edinburgh • Exeter • Glasgow • Gloucester • Hereford • Inverness • Kingston upon Hull • Lancaster • Leeds • Leicester • Lichfield • Lincoln • Lisburn • Liverpool • London • Londonderry • Manchester • Milton Keynes • Newcastle upon Tyne • Newport • Newry • Norwich • Nottingham • Oxford • Perth • Peterborough • Plymouth • Portsmouth • Preston • Ripon • Rochester • Salford • Salisbury • Sheffield • Southampton • St Albans • St Asaph • St David's • Southend-on-Sea • Stirling • Stoke-on-Trent • Sunderland • Swansea • Truro • Wakefield • Wells • Westminster • Winchester • Wolverhampton • Worcester • Wrexham • York |