Stanegate

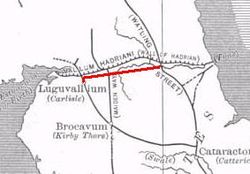

The Stanegate was an important Roman road 38 miles long running south of Hadrian's Wall, in the Roman frontier region, through Cumberland and Northumberland. It linked two forts that guarded important river crossings: Corstopitum (Corbridge) in the east, on Dere Street, and Luguualium (Carlisle) in the west. The Stanegate ran through the natural gap formed by the valleys of the Tyne and Irthing.

The Stanegate differed from most other Roman roads in that it often followed the easiest gradients, and so tends to meander, in contrast to the typical Roman road which follows an arrow-straight path even if this sometimes involves having punishing gradients to climb.[1]

It is not known what the Romans called this road not the frontier system of which it was a part.

History

When Stanegate was built is uncertain. One suggestion is that it was built under the governorship of Gnaeus Julius Agricola; he who struck deep into the Highlands of Caledonia. Others propose that it was laid down as a frontier system by the Emperor Trajan (98-117), an emperor who was energetic in building frontier fortifications for the empire. It was Trajan's successor, Hadrian, who built Hadrian's Wall some miles to the north of the Stanegate and its forts.

It is also thought that it was built as a strategic road when the northern frontier was on the line of the Forth and Clyde, and only later became part of the frontier when the Romans withdrew from Caledonia. An indication of this is that it was provided with forts at one-day marching intervals (14 Roman miles (a modern 13 miles), sufficient for a strategic non-frontier road. The forts at Vindolanda (Chesterholm) and Nether Denton have been shown to date from about the same time as Corstopitum and Luguualium, in the 70s AD and 80s AD. When the Romans decided to withdraw from Caledonia, the line of the Stanegate became the new frontier and it became necessary to provide forts at half-day marching intervals. These additional forts were Newbrough, Magnis and Brampton Old Church. It has been suggested that a series of smaller forts were built in between the 'half-day-march' forts. Haltwhistle Burn and Throp might be such forts, but there is insufficient evidence to confirm a series of such fortlets. The retreat from the far north took place in about AD105, and so the strengthening of the Stanegate defences would date from about that time.[2]

Structure

Where it left the base of Corstopitum, the Stanegate was 22 feet wide with covered stone gutters and a foundation of 6-inch cobbles with 10 inches of gravel on top.[3]

Route

The Stanegate began in the east at Corstopitum, where the important road, Dere Street headed north towards the Firth of Forth. West of Corsopitum, the Stanegate crossed the Cor Burn, and then followed the north bank of the Tyne until it reached the North Tyne near the village of Wall. A Roman bridge must have taken the road across the North Tyne, from where it headed west past the present village of Fourstones to Newbrough, where the first fort is situated, 7½ miles from Corbridge, and 6 miles from Vindolanda. It is a small fort occupying less than an acre and is in the graveyard of Newbrough church.[3]

From Newbrough, the Stanegate proceeds west, parallel to the South Tyne until it meets the next major fort, at Vindolanda (Chesterholm). From Vindolanda the Stanegate crosses the route of the present-day Military Road, built by General Wade, and passes just south of the minor fort of Haltwhistle Burn. From Haltwhistle Burn, the Stanegate continues west away from the course of the South Tyne and passes the major fort of Magnis, six and a half miles from Vindolanda and twenty miles from Corstopitum. At this point, the road is joined by the Maiden Way coming from Epiacum' (Whitley Castle) to the south.[3]

From Magnis, the road turns towards the southeast to follow the course of the River Irthing, passing the minor fort of Throp, and arriving at the major fort of Nether Denton, 4 ½ miles from Magnis and 24½ miles from Corstopitum. The fort occupies an area of about 3 acres.[3]

From Nether Denton, the road continues to follow the River Irthing and heads towards present-day Brampton, Cumberland. It passes the minor fort of Castle Hill Boothby and then, a mile east of Brampton, reaches the next major fort, that of Brampton Old Church, 6 miles from Nether Denton and 30½ miles from Corstopitum. The fort is so called because half of it is buried under Old St. Martin's church and its graveyard.[3]

From Brampton Old Church, the road crosses the River Irthing and continues east through Irthington and High Crosby. It crosses the River Eden at some point and eventually reaches the fort of Luguualium (Carlisle), 7½ miles from Brampton Old Church and 38 miles all told from Corstopitum. It has been suggested that the road may have carried on west for a further 4 or 5 miles to Kirkbride on the Solway Firth where a large camp of 5 acres has been found, but the evidence is insufficient.[3]

It has also been suggested that the Stanegate may have run eastwards from Corstopitum towards Pons Aelius; present-day Newcastle upon Tyne, but there is no evidence to support this.[2]

List of forts on the Stanegate

- Corstopitum (major fort)

- Newbrough (minor fort)

- Vindolanda (Chesterholm) (major fort)

- Haltwhistle Burn (minor fort)

- Magnis (major fort)

- Throp (minor fort)

- Nether Denton (major fort)

- Castle Hill Boothby (minor fort)

- Brampton Old Church (major fort)

- Luguualium (major fort)

Subsequent history

Much of the Stanegate provided the foundation for the Carelgate (or Carlisle Road), a mediæval road running from Corbridge market place and joining the Stanegate west of Corstopitum. The Carelgate eventually deteriorated to such an extent that it was unusable by coaches and wagons. In 1751–1752, a new Military Road was built by General George Wade in the wake of the Jacobite rising of 1745.[3]

See also

Outside links

| ("Wikimedia Commons" has material about Stanegate) |

- Location map: 55°0’19"N, 2°16’58"W

- Roman Frontiers: Stanegate

- Frontiers of Knowledge: A Research Framework for Hadrian’s Wall, Part of the Frontiers of the Roman Empire World Heritage Site – University of Durham (PDF)

References

- ↑ Raymond Selkirk (1995). On The Trail of the Legions (pages 107–120). Anglia Publishing. ISBN 1-897874-08-1.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 David J Breeze and Brian Dobson (1976). Hadrian's Wall (pages 16–24). Allen Lane. ISBN 0-14-027182-1.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Frank Graham (1979). Hadrian's Wall, Comprehensive History and Guide (pages 185–193). Frank Graham. ISBN 0-85983-140-X.