Merton College, Oxford

| Merton College Latin: Domus sive collegium scholarium de Merton in universitate Oxon[1]

| |||||||||||

|

Qui Timet Deum Faciet Bona | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Warden: | Jennifer Payne | ||||||||||

| Website: | merton.ox.ac.uk | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Location | |||||||||||

| Grid reference: | SP51730608 | ||||||||||

| Location: | 51°45’4"N, 1°15’7"W | ||||||||||

Merton College, known in full as The House or College of Scholars of Merton in the University of Oxford, is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford. Its foundation can be traced back to the 1260s when Walter de Merton, chancellor to Henry III and later to Edward I, first drew up statutes for an independent academic community and established endowments to support it. An important feature of de Merton's foundation was that this "college" was to be self-governing and the endowments were directly vested in the Warden and Fellows.[2]

By 1274, when Walter retired from royal service and made his final revisions to the college statutes, the community was consolidated at its present site in the south-east corner of the city of Oxford, and a rapid programme of building commenced. The hall and the chapel and the rest of the front quad were complete before the end of the 13th century. Mob Quad, one of Merton's quadrangles, was constructed between 1288 and 1378, and is claimed to be the oldest quadrangle in Oxford,[3] while Merton College Library, located in Mob Quad and dating from 1373, is the oldest continuously functioning library for university academics and students in the world.[4]

Like many of Oxford's colleges, Merton admitted its first mixed-sex cohort in 1979, after over seven centuries as an institution for men only.[5]

Alumni and academics past and present include five Nobel laureates, the writer J. R. R. Tolkien, who was Merton Professor of English Language and Literature from 1945 to 1959, and Liz Truss, who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in September and October 2022.[6] Merton is one of the wealthiest colleges in Oxford.

History

Foundation and origins

Merton College was founded in 1264 by Walter de Merton, Lord Chancellor and Bishop of Rochester.[7] It has a claim to be the oldest college in Oxford, a claim which is disputed between Merton College, Balliol College and University College. One argument for Merton's claim is that it was the first college to be provided with statutes, a constitution governing the college set out at its founding. Merton's statutes date back to 1264, whereas neither Balliol nor University College had statutes until the 1280s.[8]

Merton has an unbroken line of wardens dating back to 1264. Of these, many had great influence over the development of the college. Henry Savile was one notable leader who led the college to flourish in the early 17th century by extending its buildings and recruiting new fellows.[9]

In 1333, masters from Merton were among those who left Oxford in an attempt to found a new university at Stamford. The leader of the rebels was reported to be one William de Barnby, a Yorkshireman who had been fellow and bursar of Merton College.

St Alban Hall

St Alban Hall was an independent academic hall owned by the convent of Littlemore until it was purchased by Merton College in 1548 following the dissolution of the convent. It continued as a separate institution until it was finally annexed by the college in 1881, on the resignation of its last Principal, William Charles Salter.

Parliamentarian sympathies in the Civil War

During the Civil War, Merton was the only Oxford college to side with Parliament. This was due to an earlier dispute between the Warden, Nathaniel Brent, and the Visitor of Merton and Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud. Brent had been Vicar-General to Laud, who had held a visitation of Merton College in 1638, and insisted on many radical reforms: his letters to Brent were couched in haughty and decisive language.[10]

Brent, a parliamentarian, moved to London at the start of the Civil War: the college's buildings were commandeered by the Royalists and used to house much of Charles I's court when Oxford was the Royalists' capital. This included the King's French wife, Queen Henrietta Maria, who was housed in or near what is now the Queen's Room, the room above the arch between Front and Fellows' Quads. A portrait of Charles I hangs near the Queen's Room as a reminder of the role it played in his court.[citation needed]

Brent gave evidence against Laud in his trial in 1644. After Laud was executed on 10 January 1645, John Greaves, one of the subwardens of Merton and Savilian Professor of Astronomy, drew up a petition for Brent's removal from office; Brent was deposed by Charles I on 27 January 1646 and replaced by William Harvey.[10]

Thomas Fairfax captured Oxford for the Parliamentarians after its third siege in 1646 and Brent returned from London. However, in 1647, a parliamentary commission (visitation) was set up by Parliament "for the correction of offences, abuses, and disorders" in the University of Oxford. Nathaniel Brent was the president of the visitors.[10] Greaves was accused of sequestrating the college's plate and funds for King Charles I.[11] Despite a deposition from his brother Thomas, Greaves had lost both his Merton fellowship and his Savilian chair by 9 November 1648.[12]

Buildings and grounds

The "House of Scholars of Merton" originally had properties in Surrey (in present-day Old Malden) as well as in Oxford, but it was not until the mid-1260s that Walter de Merton acquired the core of the present site in Oxford, along the south side of what was then St John's Street (now Merton Street). The college was consolidated on this site by 1274, when Walter made his final revisions to the college statutes.[13]

The initial acquisition included the parish church of St John (which was superseded by the chapel) and three houses to the east of the church which now form the north range of Front Quad. Walter also obtained permission from the king to extend from these properties south to the old city wall to form an approximately square site. The college continued to acquire other properties as they became available on both sides of Merton Street. At one time, the college owned all the land from the site that is now Christ Church to the south-eastern corner of the city. The land to the east eventually became the current Fellows' garden, while the western end was leased by Warden Richard Rawlins in 1515 for the foundation of Corpus Christi (at an annual rent of just over £4).[14]

Chapel

By the late 1280s, the old church of St John the Baptist had fallen into "a ruinous condition",[15] and the college accounts show that work on a new church began in about 1290. The present choir, with its enormous east window, was complete by 1294. The window is an important example (because it is so well dated) of how the strict geometrical conventions of the Early English Period of architecture were beginning to be relaxed at the end of the 13th century.[16] The south transept was built in the 14th century, the north transept in the early years of the 15th. The great tower was complete by 1450. The chapel replaced the parish church of St. John and continued to serve as the parish church as well as the chapel until 1891. It is for this reason that it is generally referred to as Merton Church in older documents, and that there is a north door into the street as well as doors into the college. This dual role also probably explains the enormous scale of the chapel, which in its original design was to have a nave and two aisles extending to the west.[17]

A new choral foundation was established in 2007, providing for a choir of sixteen undergraduate and graduate choral scholars singing from October 2008.

A spire from the chapel has resided in Pavilion Garden VI of the University of Virginia since 1928, when "it was given to the University to honor Jefferson's educational ideals."

Front quad and the hall

The hall is the oldest surviving college building, originally completed before 1277, but apart from the fine mediæval ironwork on the door, almost no trace of the ancient structure has survived the successive reconstruction efforts; first by James Wyatt in the 1790s and then again by Gilbert Scott in 1874, whose work included the “handsome oak roof”.[18] The hall is still used daily for meals in term time. It is not usually open to visitors.[19]

Front quad itself is probably the earliest collegiate quadrangle, but its informal, almost haphazard, pattern cannot be said to have influenced designers elsewhere. A reminder of its original domestic nature can be seen in the north-east corner where one of the flagstones is marked "Well". The quad is formed of what would have been the back gardens of the three original houses that Walter acquired in the 1260s.[20]

Mob Quad and library

Visitors to Merton are often told that Mob Quad is the oldest quadrangle of any Oxford or Cambridge college and set the pattern for future collegiate architecture. It was built in three phases: 1288–1291, 1304–1311, and finally completed with the Library in 1373–1378.[21] But Merton's own Front Quad was probably enclosed earlier, albeit with a less unified design.[22] Other colleges can point to similarly old and unaltered quadrangles, for example Old Court at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, built c.1353–1377.[23]

Fellows' Quad

The grandest quadrangle in Merton is the Fellows' Quadrangle, immediately south of the hall. The quad was the culmination of the work undertaken by Henry Savile at the beginning of the 17th century. The foundation stone was laid shortly after breakfast on 13 September 1608 (as recorded in the college Register), and work was complete by September 1610 (although the battlements were added later).[24] The southern gateway is surmounted by a tower of the four Orders, probably inspired by Italian examples that Warden Savile would have seen on his European travels. The main contractors were from Yorkshire (as was Savile); John Ackroyd and John Bentley of Halifax supervised the stonework, and Thomas Holt the timber. This group were also later employed to work on the Bodleian Library and Wadham College.[25]

Gardens

The garden fills the southeastern corner of the old walled city of Oxford. The walls may be seen from Christ Church Meadows and Merton Field (now used by Magdalen College School, Oxford as a playing field for cricket, rugby, and football). The gardens are notable for a mulberry tree planted in the early 17th century, an armillary sundial, an extensive lawn, a Herma statue, and the old Fellows' Summer House (now used as a music room and rehearsal space).

Gallery

| ("Wikimedia Commons" has material about Merton College, Oxford) |

-

Merton College Chapel

-

Merton from Broad Walk

-

The front quad and the main entrance to the college

-

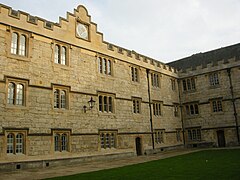

Fellows' quad

-

Mob quad

-

Merton from St Mary's Church

-

Merton from across the Christ Church Meadow

-

View of the chapel tower

-

The south wing of the Upper Library

-

Old book bindings at the Merton College Library

-

Bookshelves in the Library

-

Globe dating from the 16th century

-

Library

Traditions

At the 'Time Ceremony', students dressed in formal academic dress walk backwards around the Fellows' Quad drinking port. Traditionally participants also held candles, but this practice has been abandoned in recent years. Many students have now adopted the habit of linking arms and twirling around at each corner of the quad. The alleged purpose of this tradition is to maintain the integrity of the space–time continuum during the transition from British Summer Time to Greenwich Mean Time, which occurs in the early hours of the last Sunday in October. However, the ceremony (invented by two undergraduates in 1971) mostly serves as a spoof of other Oxford ceremonies, and historically as a celebration of the end of the experimental period of British Standard Time from 1968 to 1971 when the UK stayed one hour ahead of GMT all year round. There are three toasts associated with the ceremony. The first is "to a good old time!"; the second, a joint toast to the sundial and the nearby mulberry tree (morus nigra), "o tempora, o more"; and the third, "long live the counter-revolution!".[26]

Merton is the only college in Oxford to hold a triennial winter ball, instead of the more common Commemoration ball. The most recent of these was held on 26 November 2022.[27]

Societies

Merton has a number of drinking and dining societies, along the lines of other colleges. These include the all-male Myrmidons, the female-equivalent Myrmaids and L'Ancien Régime. The Myrmidon club is open to all members of the college in the present day, male or female, and hosts termly black tie events.

Merton is host to a number of subject-specific societies, the most notable being the Halsbury Society (Law)[28] and the Chalcenterics (Classics).[29] Other academic societies include the Neave Society, which aims to discuss and debate political issues, and the Bodley Club, founded in 1894 as a forum for undergraduate papers on literature but now a speaker society.[30]

The Bodley Club is a speaker society at Merton College, Oxford. Founded in 1894 as a forum in which undergraduates delivered academic papers on literature, the club has changed form over the years, and was reformed in the 1980s as a speaker society. All members of the college, and usually members of the university as a whole, are invited to their events.

Outside links

| ("Wikimedia Commons" has material about Merton College, Oxford) |

References

- ↑ Coke, Edward (1810). The Reports of Sir Edward Coke, Knt: In Thirteen Parts, Volume 5. London: G. Woodfall. p. 476. https://books.google.com/books?id=PSdEAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA1-PA476.

- ↑ See Martin & Highfield, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Bott, p. 16.

- ↑ "Library & Archives". http://www.merton.ox.ac.uk/library-and-archives.

- ↑ "750 Years of Merton College - A Timeline" (in en). https://www.merton.ox.ac.uk/merton-timeline.

- ↑ Grotta, Daniel (28 March 2001). J.R.R. Tolkien Architect of Middle Earth. Running Press. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-7624-0956-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=9LHQvq6P5qIC&pg=PA64. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ↑ "The history of Merton" (in en-GB). https://www.merton.ox.ac.uk/about/history-merton.

- ↑ Hastings, Rashdall (1895). The Universities Of Europe In The Middle Ages, Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford UP. pp. 177, 181, 192. https://archive.org/details/universitiesofeu03hast/page/192/mode/2up?q=. Retrieved 31 Jan 2022.

- ↑ "Savile, Henry (1549-1622)". en.wikisource.org. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Savile,_Henry_(1549-1622)_(DNB00).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Dictionary of National Biography, Vol 6 : Brent, Nathaniel, pp. 262–4

- ↑ Ward, John (1740). The Lives of the Professors of Gresham College, to which is prefixed the Life of the Founder, Sir Thomas Gresham, pp. 144–146 London: John Moore. Google Books full view, retrieved 10 May 2011

- ↑ Biographia Britannica Or, The Lives of the Most Eminent Persons who Have Flourished in Great Britain and Ireland, from the Earliest Ages, Down to the Present Times, Vol. 4. London. 1757. p. 2275. https://books.google.com/books?id=Y4lDAAAAcAAJ&dq=biographica+britannica+greaves&pg=PA2274. Retrieved 31 Jan 2022.

- ↑ George, Brodrick (1885). Memorials of Merton College. Oxford: Clarendon. p. 6. https://books.google.com/books?id=BShKAQAAMAAJ&dq=site+of+merton+college+1274&pg=PA391. Retrieved 31 Jan 2022.

- ↑ See Bott, p.4

- ↑ Anthony Wood, quoted in Bott, p.24

- ↑ Pevsner, p.25

- ↑ See Bott, pp.24–37

- ↑ Bott, p.10

- ↑ "Information for Visitors". merton.ox.ac.uk. https://www.merton.ox.ac.uk/visitor-information.

- ↑ Bott, p.4

- ↑ Bott, p.16

- ↑ Also Bott, p.10 slightly contradicting himself.

- ↑ "The Courts of Corpus Christi". https://www.corpus.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/the_courts_of_corpus_christi.pdf.

- ↑ Bott, p.37

- ↑ Martin & Highfield, p.163

- ↑ "Merton Miscellany". https://barrypressblog.wordpress.com/.

- ↑ "Merton Winter Ball". Merton College. https://www.merton.ox.ac.uk/event/merton-winter-ball.

- ↑ "Studying Law at Merton". ox.ac.uk. http://www.merton.ox.ac.uk/admissions/ug_subj_law.shtml.

- ↑ "Studying Classics & joint schools at Merton". ox.ac.uk. http://www.merton.ox.ac.uk/admissions/ug_subj_classics.shtml.

- ↑ "Clubs & Societies/" (in en-US). http://mertonmcr.org/resources/clubs-societies/.

- Bott, A. (1993). Merton College: A Short History of the Buildings. Oxford: Merton College. ISBN 0-9522314-0-9.

- Martin, G.H. & Highfield, J.R.L. (1997). A History of Merton College. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-920183-8.

- Nikolaus Pevsner: The Buildings of England: Oxfordshire, 1974 Penguin Books ISBN 978-0-300-09639-2

| Colleges of the University of Oxford | |

|---|---|

| Colleges:

All Souls • Balliol • Brasenose • Christ Church • Corpus Christi • Exeter • Green Templeton • Harris Manchester • Hertford • Jesus • Keble • Kellogg • Lady Margaret Hall • Linacre • Lincoln • Magdalen • Mansfield • Merton • New College • Nuffield • Oriel • Pembroke • The Queen's • Reuben • St Anne's • St Antony's • St Catherine's • St Cross • St Edmund Hall • St Hilda's • St Hugh's • St John's • St Peter's • Somerville • Trinity • University • Wadham • Wolfson • Worcester |

|

| Permanent private halls:

Blackfriars • Campion Hall • Regent's Park College • St Benet's Hall • St Stephen's House • Wycliffe Hall | |