Liverpool Cathedral: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|os grid ref=SJ354894 | |os grid ref=SJ354894 | ||

|latitude=53.397509 | |latitude=53.397509 | ||

|longitude-2.973320 | |longitude=-2.973320 | ||

|architect=Giles Gilbert Scott | |architect=Giles Gilbert Scott | ||

|style=Gothic Revival | |style=Gothic Revival | ||

Revision as of 16:01, 14 August 2016

| Liverpool Cathedral | |

|

Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool | |

|---|---|

|

Liverpool, Lancashire | |

| Status: | cathedral |

Liverpool Cathedral | |

| Church of England | |

| Diocese of Liverpool | |

| Location | |

| Grid reference: | SJ354894 |

| Location: | 53°23’51"N, 2°58’24"W |

| History | |

| Built 1904–1978 | |

| Gothic Revival | |

| Information | |

| Website: | liverpoolcathedral.org.uk |

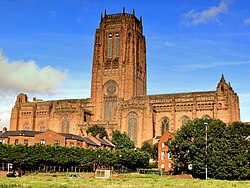

Liverpool Cathedral is the cathedral of the Diocese of Liverpool in the Church of England and the seat of the Bishop of Liverpool. It was built on St James's Mount in Liverpool between 1910 and 1978; a lengthy period interrupted by war and economic depression. The official name of the cathedral is the Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool, as is recorded in the Document of Consecration, but is also called 'the Cathedral Church of the Risen Christ, Liverpool'.[1]

The cathedral is based on a design by Giles Gilbert Scott. The total external length of the building, including the Lady Chapel is 207 yards, making it the longest cathedral in the world. Its internal length is 160 yards. In terms of overall volume, Liverpool Cathedral contests with the incomplete Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City for the title of largest Anglican church building in the world (depending on which dimensions are counted).[2]

With a height of 331 feet, it is also one of the world's tallest non-spired church buildings and the third-tallest structure in the city of Liverpool]]. The cathedral is designated a Grade I listed building.[3]

The Anglican cathedral is one of two cathedrals in the city, the other being the Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Liverpool, standing half a mile to the north. The two cathedrals are linked by Hope Street, which takes its name from William Hope, a local merchant whose house stood here, and was named long before either of the rival cathedrals was built.

History

Background

The process of founding a cathedral was slow. When John Charles Ryle was installed as the first Bishop of Liverpool in 1880 he had no Cathedral, but the parish church of St Peter's in Church Street was named a "pro-cathedral". It was however too small for major church events, and moreover was, in the words of the Rector of Liverpool, "ugly & hideous".[4] In 1885 an Act of Parliament authorised the building of a Cathedral on the site of the existing St John's Church, adjacent to St George's Hall.[5] A competition was held for the design, and won by Sir William Emerson. The site proved unsuitable for the erection of a building on the scale proposed, and the scheme was abandoned.[5]

In 1900 Francis Chavasse succeeded Ryle as Bishop, and immediately revived the project to build a Cathedral.[6] There was some opposition from among members of Chavasse's diocesan clergy, who maintained that there was no need for an expensive new Cathedral. The architectural historian John Thomas argues that this reflected "a measure of factional strife between Liverpool Anglicanism's very Evangelical or Low Church tradition, and other forces detectable within the religious complexion of the new diocese." Chavasse, though himself an Evangelical, regarded the building of a great church as "a visible witness to God in the midst of a great city".[7] Eventually, after much debate St James's Mount was chosen. A historian of the Cathedral, Vere Cotton, wrote in 1964:

Looking back after an interval of sixty years, it is difficult to realise that any other decision was even possible. With the exception of Durham, no English Cathedral is so well placed to be seen to advantage both from a distance and from its immediate vicinity. That such a site, convenient to yet withdrawn from the centre of the city … dominating the city and clearly visible from the river, should have been available is not the least of the many strokes of good fortune which have marked the history of the Cathedral.

Fund-raising began, and new enabling legislation was passed by Parliament, The Liverpool Cathedral Act 1902 authorising the purchase of the site and the demolition of St Peter's to provide the endowment of the new Cathedral's chapter: St Peter's Church was finally demolished in 1922.[8]

Competitions

Liverpool was to have the first wholly new ground-up cathedral in the Church of England since the 16th century Reformation, apart from St Paul’s in London, which replaced an earlier cathedral, and Truro, which replaced an earlier parish church, and it was to be on a grander scale than either of these. In late 1901, two well-known architects were appointed as assessors for an open competition for the design of the new cathedral: G F Bodley, a Gothic revivalist,[9] and R Norman Shaw, an eclectic architect.[10]

It was stipulated that the designs were to be in the Gothic style,[11] not without controversy from modernists (a "worn-out flirtation in antiquarianism, now relegated to the limbo of art delusions")[12] The competition attracted 103 entries, from architects including Temple Moore, Charles Rennie Mackintosh,[13] Charles Reilly,[14] and Austin and Paley.[15]

In 1903, the assessors recommended a proposal submitted by the 22-year-old Giles Gilbert Scott, who was still an articled pupil working in Temple Moore's practice,[16] and had no existing buildings to his credit. He told the assessors that so far his only major work had been to design a pipe-rack.[17] The choice of winner was even more contentious with the Cathedral Committee when it was discovered that Scott was a Roman Catholic, but the decision stood.[16] Scott's first design was overseen by Bodley, until the latter’s death in 1907, leaving Scott in charge[18] as the sole architect. This position allowed Scott to resubmit an entirely new design in 1910; a radical change approved only when Scott had provided the fine detail.

In addition to changes in the exterior, Scott's new plans provided more interior space.[19] At the same time Scott modified the decorative style, losing much of the Gothic detailing and introducing a more modern, monumental style.[20]

The Lady Chapel (originally intended to be called the Morning Chapel),[7] the first part of the building to be completed, was consecrated in 1910 by Bishop Chavasse in the presence of two Archbishops and 24 other Bishops.[21] The date, 29 June – St Peter's Day, was chosen to honour the pro-cathedral, now due to be demolished.[22] The Manchester Guardian described the ceremony:

The Bishop of Liverpool knocked on the door with his pastoral staff, saying in a loud voice, "Open ye the gates." The doors having been flung open, the Earl of Derby, resplendent in the golden robes of the Chancellor of Liverpool University, presented Dr. Chavasse with the petition for consecration. … The Archbishop of York, whose cross was carried before him and who was followed by two train-bearers clad in scarlet cassocks, was conducted to the sedilla, and the rest of the Bishops, with the exception of Dr. Chavasse, who knelt before his episcopal chair in the sanctuary, found accommodation in the choir stalls.[23]

The richness of the décor of the Lady Chapel may have dismayed some of Liverpool's Evangelical clergy. Thomas suggests that they were confronted with "a feminized building which lacked reference to the 'manly' and 'muscular Christian' thinking which had emerged in reaction to the earlier feminization of religion."[7] He adds that the building would have seemed to many to be designed for Anglo-Catholic worship.[7]

Second phase

Work was severely limited during the First World War, with a shortage of manpower, materials and donations.[24] By 1920, the workforce had been brought back up to strength and the stone quarries at Woolton, source of the pinkish-red sandstone for most of the building, reopened.[24] The first section of the main body of the Cathedral was complete by 1924. It comprised the chancel, an ambulatory, chapter house and vestries.[25] The section was closed with a temporary wall, and on 19 July 1924, the 20th anniversary of the laying of the foundation stone, the Cathedral was consecrated in the presence of King George V and Queen Mary, and Bishops and Archbishops from around the globe.[24] Major works ceased for a year while Scott once again revised his plans for the next section of the building: the tower, the under-tower and the central transept.[26] The tower in his final design was higher and narrower than his 1910 conception.[27]

From July 1925 work continued steadily, and it was hoped to complete the whole section by 1940.[28] The outbreak of Second World War in 1939 caused similar problems to those of the earlier war. The workforce dwindled from 266 to 35; moreover, the building was damaged by German bombs.[29] Despite these vicissitudes, the central section was complete enough by July 1941 to be handed over to the Dean and Chapter. Scott laid the last stone of the last pinnacle on the tower on 20 February 1942.[30] No further major works were undertaken during the rest of the war. Scott produced his plans for the nave in 1942, but work on it did not begin until 1948.[31] The bomb damage, particularly to the Lady Chapel, was not fully repaired until 1955.[32]

Completion

Scott died in 1960. The first bay of the nave was then nearly complete, and was handed over to the Dean and Chapter in April 1961. Scott was succeeded as architect by Frederick Thomas.[33] Thomas, who had worked with Scott for many years, drew up a new design for the west front of the cathedral. The Guardian commented, "It was an inflation beater, but totally in keeping with the spirit of the earlier work, and its crowning glory is the Benedicite Window designed by Carl Edwards and covering 1,600 sq. ft."[34]

The completion of the building was marked by a service of thanksgiving and dedication in October 1978, attended by Queen Elizabeth II.[35]

Completed building

The Cathedral's dimensions are:

- Length: 619 feet

- Area: 104,274 square feet

- Height of tower: 331 feet

- Choir vault: 116 feet

- Nave vault: 120 feet

- Under tower vault: 175 feet

- Tower arches: 107 feet

The cathedral was built mainly of local sandstone quarried from the South Liverpool suburb of Woolton. The last sections (The Well of the Cathedral at the west end in the 1960s and 1970s) used the closest matching sandstone that could be found from other NW quarries once the supply from Woolton had been exhausted.

The belltower is the largest, and also one of the tallest, in the world. It houses the world's highest (220 feet) and heaviest (16.5 tons) ringing peal of bells, and the third-heaviest bourdon bell (14.5 tons) in the United Kingdom.[36]

Services and other uses

The cathedral holds daily worship and Holy Communion, and has a regular Sunday congregation. Since early 2011, the Cathedral has also offered a regular, more informal form of cafe-style worship called "Zone 2", running parallel to its main Sunday Eucharist each week and held in the lower rooms in the Sir Giles Gilbert Scott Function Suite (formerly The Western Rooms). Sundays are supported on each occasion during term time by the Cathedral choir.[37]

The Liverpool St. Andrew's congregation of the Church of Scotland uses the Radcliffe Room of the Cathedral for Sunday services.

The building also plays host to a wide range of events and special services including concerts, academic events involving local schools, graduations, exhibitions, family activities, seminars, conferences, corporate events, commemorative services, anniversary services and many more. Its maximum capacity for any major event including special services is 3,500 standing, or about 2,300 fully seated. The ground floor of the Cathedral is fully accessible.

Liverpool Cathedral has its own specialist constabulary to keep watch on an all-year 24-hour basis. The Liverpool Cathedral Constables together with the York Minster Police and several other cathedrals' constable units are members of the Cathedral Constables' Association.[38]

Music

The organ, built by Henry Willis & Sons, is the largest pipe organ in the UK with two five-manual consoles, 10,268 pipes and a trompette militaire.[39] There is an annual anniversary recital on the Saturday nearest to 18 October, the date of the organ's consecration. There is a two-manual Willis organ in the Lady Chapel.[40][41]

Artists and sculptors

In 1931, Scott asked Edward Carter Preston to produce a series of sculptures for Liverpool Cathedral. The project was an immense undertaking which occupied the artist for the next thirty years. The work for the Cathedral included fifty sculptures, ten memorials and several reliefs. Many inscriptions in the Cathedral were jointly written by Dean Dwelly and the sculptor who subsequently carved them.

In 1993 "The Welcoming Christ", a large bronze sculpture by Dame Elisabeth Frink, was installed over the outside of the West Door of the Cathedral.[42] This was one of her last completed works, installed within days of her death.[43]

In 2003 the Liverpool artist, Don McKinlay, who knew Carter Preston from his youth, was commissioned by the Cathedral to model an infant Christ to accompany the 15th century Madonna by Giovanni della Robbia Madonna now situated in the Lady Chapel.[44]

In 2008 a work entitled "For You" by Tracey Emin was installed at the West end of Cathedral the below the Benedicite window. The pink neon sign reads "I felt you and I knew you loved me", and was installed when Liverpool became European Capital of Culture. The work was originally intended to be a temporary installation for one month as part of the Capital of Culture programme, but is now a permanent feature.[42]

Another work by Emin, "The Roman Standard" takes the form of a small bronze sparrow on a metal pole, and was installed in 2005 outside the Oratory Chapel close to the west end of the Cathedral.[45] The sparrow was stolen (twice) in 2008, but on both occasions was returned and replaced.[46]

Stained glass

The firm of James Powell and Sons (Whitefriars), Ltd., of London, provided most of the stained glass designs. John William Brown (1842–1928) designed the Te Deum window in the east end of the Cathedral, as well as the original windows for the Lady Chapel, which was heavily damaged during German bombing raids in 1940. The glass in the Lady Chapel was replaced with designs, based on the originals, by James Humphries Hogan (1883–1948). He was one of the most prolific of the Powell and Sons designers; his designs can also be seen in the large north and south windows in the central space of the cathedral (each 100 feet tall). Later artists include William Wilson (1905–1972), who began his work at Liverpool Cathedral after the death of Hogan, Herbert Hendrie (1887–1946), and Carl Edwards (1914–1985), who designed the Benedicite window in the west front.

Outside links

| ("Wikimedia Commons" has material about Liverpool Cathedral) |

- Liverpool Pictorial Images of Liverpool Anglican cathedral

- Liverpool Cathedral website

- http://choral-evensong.spaces.live.com/ [website containing daily Cathedral blog, and all sermons, talks, lectures and courses given in the Cathedral in text and mp3 file format

- The Liverpool Shakespeare Festival Annual theatrical performance inside the Cathedral

- Virtual Tours of Liverpool Cathedral Virtual Tours of Liverpool Cathedral

- New Bridge design

- Description and pictures of the cathedral organ.

- Details of the main organ from the National Pipe Organ Register

- Details of the organ in the Lady Chapel from the National Pipe Organ Register

- Details of the Cathedral bells from Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers

- Interview with Canon Justin Welby, dean of Liverpool Cathedral

- St. Andrew's Church of Scotland Liverpool website

References

- ↑ The Form and Order of the Consecration of the Cathedral Church of Christ in Liverpool, 19 July 1924

- ↑ Quirk, Howard E., The Living Cathedral: St. John the Divine: A History and Guide (New York: The Crossroad Publishing Co., 1993), p. 15-16.

- ↑ National Heritage List 1361681: Anglican Cathedral Church of Christ

- ↑ "History", Liverpool Cathedral, accessed 2 October 2011

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Cotton, p. 1

- ↑ Bailey and Millington, p. 48

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Thomas, John

- ↑ "St Peter’s Church, Church St, Liverpool". http://www.lan-opc.org.uk/Liverpool/Liverpool-Central/stpeter/stpeter.html. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ↑ Hall, Michael. "Bodley, George Frederick (1827–1907)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 2 October 2011 (subscription required)

- ↑ Saint, Andrew. "Shaw, Richard Norman (1831–1912)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; accessed 2 October 2011 (subscription required)

- ↑ Shallcross, T Myddelton. "The Proposed New Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 8 October 1901, p. 13

- ↑ "Concordia", "Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 19 October 1901, p. 11

- ↑ "Design for Liverpool Anglican Cathedral competition: south elevation 1903" Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, accessed 2 October 2011

- ↑ Powers, p. 2

- ↑ Brandwood et al. pp. 162–164

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Stamp. Gavin. "Scott, Sir Giles Gilbert (1880–1960)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 2 October 2011 (subscription required)

- ↑ "Liverpool's 75-year-old infant", The Guardian, 21 October 1978, p. 9

- ↑ Cotton, p. 22

- ↑ Cotton pp. 28, 30 and 32

- ↑ Cotton, pp. 29–30

- ↑ Forwood, William. "Liverpool Cathedral – Consecration of the Lady Chapel", The Times, 30 June 1910, p. 9

- ↑ "Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 30 June 1910, p. 11

- ↑ "Liverpool Cathedral – Consecration of the Lady Chapel", The Manchester Guardian, 30 June 1910, p. 7

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Cotton, p. 6

- ↑ "Liverpool Cathedral", The Times, 19 June 1924, p. 13

- ↑ Cotton, p. 7

- ↑ Cotton, p. 32

- ↑ Cotton, p. 8

- ↑ Cotton, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Cotton, p. 10

- ↑ Cotton, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Cotton, p. 11.

- ↑ McNay, Thomas. "Liverpool's Anglican Cathedral", The Guardian, 24 October 1978, p. 8

- ↑ Riley, Joe. "Finished – but for the way in to the nave", The Guardian, 25 October 1978, p. 8

- ↑ Chartres, John. "New Liverpool Anglican cathedral dedicated", The Times, 26 October 1978, p. 2

- ↑ "Cathedral", Liverpool Cathedral, accessed 3 October 2011

- ↑ "Service Times", Liverpool Cathedral, accessed 3 October 2011

- ↑ The Cathedral Constables' Association, accessed 22 June 2012

- ↑ "The Organ in the Anglican Cathedral, Liverpool". http://www.liv.ac.uk/~spmr02/organ/anglican.html.

- ↑ Cotton, pp. 159–164

- ↑ "The Lady Chapel Organ in the Anglican Cathedral, Liverpool". http://www.liv.ac.uk/~spmr02/organ/ladychapel.html.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "Art in the Cathedral". http://www.liverpoolcathedral.org.uk/home/about-us/art-in-the-cathedral.aspx. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

- ↑ Pepin, David (2004). Discovering Cathedrals. Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire, UK: Shire Publications. https://books.google.com/books?id=Qxs7peepspMC&pg=PA87&lpg=PA87. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

- ↑ "Hidden gems", Daily Post, Liverpool, 6 November 2010

- ↑ "Emin unveils sparrow sculpture". http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/merseyside/4293245.stm. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ↑ "Stolen Emin sparrow returns again". http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/merseyside/7614218.stm. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- Bailey, F A; R Millington (1957). The Story of Liverpool. Liverpool: Corporation of the City of Liverpool. OCLC 19865965.

- Brandwood, Geoff; Austin, Tim; Hughes, John; Price, James (2012). The Architecture of Sharpe, Paley and Austin. Swindon: English Heritage. ISBN 978-1-84802-049-8.

- Cotton, Vere E (1964). The Book of Liverpool Cathedral. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. OCLC 2286856.

- Powers, Alan (1996). "Liverpool and Architectural Education in the Early Twentieth Century". in Sharples, Joseph. Charles Reilly & the Liverpool School of Architecture 1904–1933. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 1–23. ISBN 0-85323-901-0.

Further reading

- Cotton, Vere E (1964). The Liverpool Cathedral Official Handbook. Liverpool: Littlebury Bros for Liverpool Cathedral Committee. OCLC 44551681.

- Vincent, Noel (2002). The Stained Glass of Liverpool Cathedral. Norwich: Jarrold. ISBN 0-7117-2589-6.