Ossory: Difference between revisions

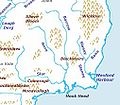

Created page with "right|thumb|220px|A map of Ireland showing Osraige in the 10th century {{county|Kilkenny}} '''Ossory''' is a traditional region of Ireland,..." |

|||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

* Ó Néill, Pádraig. "Osraige", in Seán Duffy (ed.), ''Mediæval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge. 2005. p. 358 | * Ó Néill, Pádraig. "Osraige", in Seán Duffy (ed.), ''Mediæval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge. 2005. p. 358 | ||

* Radner, Joan. ''Writing History: Early Irish Historiography and the Significance of Form'', in 'Celtica 23' (1999); p. 312–325 | * Radner, Joan. ''Writing History: Early Irish Historiography and the Significance of Form'', in 'Celtica 23' (1999); p. 312–325 | ||

[[Category:Irish kingdoms]] | |||

[[Category:County Kilkenny]] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:01, 6 December 2021

Ossory is a traditional region of Ireland, anciently a kingdom into the Middle Ages, and comprising what ae now County Kilkenny and western County Laois, and corresponding to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Ossory. This was the home of the Osraige people: it existed from around the first century until the Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century. Ossory was ruled by the Dál Birn dynasty, whose mediæval descendants assumed the surname Mac Giolla Phádraig, which became in Norman days 'Fitzpatick'.

The kingdom was known as Osraige in Old Irish.[1] or Osraighe in Classical Irish, and now as Osraí (in Modern Irish)

According to tradition, Osraige was founded by Óengus Osrithe in the 1st century and was originally within the province of Leinster. In the 5th century, the Corcu Loígde of Munster displaced the Dál Birn and brought Osraige under Munster's direct control. The Dál Birn returned to power in the 7th century, though Osraige remained nominally part of Munster until 859, when it achieved formal independence under the powerful king Cerball mac Dúnlainge. Osraige's rulers remained major players in Irish politics for the next three centuries, though they never vied for the High Kingship.

In the early 12th century, dynastic infighting fragmented the kingdom, and it was re-adjoined to Leinster. The Normans under Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, known as Strongbow, invaded Ireland beginning in 1169, and most of Osraige collapsed under pressure from Norman leader William Marshal. The northern part of the kingdom, eventually known as Upper Ossory, survived intact under the hereditary lordship until the reign of King Henry VIII of England, when it was formally incorporated as a barony of the same name.

Geography

The ancient Osraige inhabited the fertile land around the River Nore valley, occupying nearly all of what is modern County Kilkenny and the western half of neighbouring County Laois. To the west and south, Osraige was bounded by the River Suir and what is now Waterford Harbour; to the east, the watershed of the River Barrow marked the boundary with Leinster (including Gowran); to the north, it extended into and beyond the Slieve Bloom Mountains. These three principal rivers- the Nore, the Barrow, and the Suir, which unite just north of Waterford City, were collectively known as the "Three Sisters" (Cumar na dTrí Uisce).[2]

Like many other Irish kingdoms, the tribal name of Osraighe also came to be applied to the territory they occupied; thus, wherever the Osraige dwelt became known as Osraige. The kingdom's most significant neighbours were the Loígis, Uí Ceinnselaig and Uí Bairrche of Leinster to the north and east and the Déisi, Eóganacht Chaisil and Éile of Munster to the south and west.[3] Some of the highest points of land are Brandon Hill (County Kilkenny) and Arderin (on the Laois-Offaly border). The ancient Slige Dala road ran south-west through northern Osraige from the Hill of Tara towards Munster; which later gave its name to the mediæval Ballaghmore Castle.[4] Another ancient road, the Slighe Cualann cut into southeast Osraige west of present-day Ross, before turning south to present-day Waterford.

-

Topography of Osraige; note location of the "Three Sisters".

-

The source of the River Barrow in the Slieve Bloom Mountains

-

The River Nore

-

The River Suir

-

The Slieve Blooms

-

Brandon Hill, the highest elevation in Kilkenny

History

Origins and prehistory

The tribal name Osraige means "people of the deer", and is traditionally claimed to be taken from the name of the ruling dynasty's semi-legendary pre-Christian founder, Óengus Osrithe.[5][6] The Osraige were probably either a southern branch of the Ulaid or Dál Fiatach of Ulster,[7] or close kin to their former Corcu Loígde allies.[8] In either case it would appear they should properly be counted among the Érainn. Some scholars believe that the Ō pedigree of the Osraige is a fabrication, invented to help them achieve their goals in Leinster. Francis John Byrne suggests that it may date from the time of Cerball mac Dúnlainge.[9] The Osraighe themselves claimed to be descended from the Érainn people, although scholars propose that the Ivernic groups included the Osraige. Prior to the coming of Christianity to Ireland, the Osraige and their relatives the Corcu Loígde appear to have been the dominant political groups in Munster, before the rise of the Eóganachta marginalized them both.[10]

Ptolemy's 2nd-century map of Ireland places a tribe he called the "Usdaie" roughly in the same area that the Osraige occupied.[11] The territory indicated by Ptolemy likely included the major late Iron Age hill-fort at Freestone Hill and a 1st-century Roman burial site at Stonyford, both in County Kilkenny.

Due to inland water access via the Nore, Barrow and Suir rivers, the Osraige may have experienced greater intercourse with Britain and the continent, and there appears to have been some heightened Roman trading activity in and around the region. Such contact with the Roman world may have precipitated wider exposure and later conversion to Early Christianity.

From the fifth century, the name Dál Birn ("the people of Birn"; sometimes spelt dál mBirn) appears to have emerged as the name for the ruling lineage of Osraige, and this name remained in use through to the twelfth century. From this period, Osraige was originally within the sphere of the province of Leinster.

Later history

By the early-12th century, fighting had erupted within the dynasty and split the kingdom into three territories. In 1103, Gilla Pátraic Ruadh, king of Osraige and many of the Ossorian royal family were killed on campaign in the north of Ireland.[12] Two new claimants to the throne then emerged, both scions of the Mac Giolla Phádraig clan. Domnall Ruadh Mac Gilla Pátraic was the king of greater Osraige, often called Tuaisceart Osraige ("North Osraige") or Leath Osraige ("Half-Osraige"); and Cearbhall mac Domnall mac Gilla Pátraic in Desceart Osraige ("South Osraige"), a smaller portion of the southernmost part of Osraige bordering Waterford. Additionally, the Ua Caellaighe clan of Mag Lacha and Ua Foircheallain in the extreme north Osraige declared their independence from Mac Giolla Phádraig rule under Fionn Ua Caellaighe. Thus the north and south fringes of the kingdom broke apart from the centre, each with subsequent competing dynasts until the arrival of the Normans. While the north and south extremities of the kingdom were broken away, the majority of central Osraige around the fertile Nore valley maintained greater stability and is most often referred to simply as "Osraige" in most annals for the period.

Despite its fracturing, Osraige was still powerful enough to oppose and inflict defeats upon Leinster.[13] As retribution in 1156–7, the high king Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn led a massive campaign of destruction deep into Osraige, laying waste to it from end to end, and officially subjected it to Leinster.[14][15]

Decline during the Norman Invasion (1165–1194)

Much of the background drama and initial action of the Norman advance played out on the battlefields and highways of Ossory. The kingdoms of Ossory and Leinster had also witnessed increased mutual hostility prior to the Normans. Significantly, Diarmaid Mac Murchadha, the man who would one day become king of Leinster and invite the Normans into Ireland, was himself fostered as a youth in north Ossory, in the territory of the Ua Caellaighes of Dairmag Ua nDuach who sought to undermine their Mac Giolla Phádraig overlords. In the 1150s, high king Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn made a devastating punitive campaign on the divided Osraige, burning and pillaging the whole kingdom and subjected it to Leinster overlordship. Thus, Diarmaid Mac Murchadha came to intervene several times in the disputes of Ossorian succession. After Mac Murchadha's exile and return in 1167, tension was heightened between Osraige and Leinster by the blinding of Mac Murchadha's son and heir, Éanna mac Diarmat by the prince of greater Osraige, king Donnchad Mac Giolla Phádraig.[16] Mac Murchadha's initial mercenary force under Robert FitzStephen landed close to the border of Ossory at Bannow, took Wexford and immediately turned west to invade Ossory, acquiring hostages as a nominal token of submission.[17] Later still, another auxiliary force under Raymond FitzGerald (le Gros) landed just opposite Ossory's border at Waterford, and won a skirmish with its inhabitants.[18] By 1169, Strongbow himself had also landed with a major force outside of Waterford, married Mac Murchadha's daughter Aoife and sacked the city.[19] Later that year, a major conflict was fought in the woods of Ossory near Freshford when Mac Murchadha and his Norman allies under Robert FitzStephen, Meiler FitzHenry, Maurice de Prendergast, Miles FitzDavid, and Hervey de Clare (Montmaurice) defeated a numerically superior force under Domnall Mac Giolla Phádraig, king of greater-Osraige, at the pass of Achadh Úr following a feigned retreat in a three-day battle. Shortly thereafter, de Prendergast and his contingent of Flemish soldiers defected from Mac Murchada's camp and joined king Domnall's forces in Ossory before quitting Ireland for a time.

In 1170, MacMurchada died, leaving Strongbow as the King of Leinster, which in his understanding, included Osraige. At Threecastles, Strongbow and Mac Giolla Phádraig agreed to the Treaty of Odogh (Ui Duach) in 1170, in which de Prendergast saved the life of the prince of Ossory from a treacherous assassination.[20] Osraige was afterwards invaded by Strongbow's troops and an Ua Briain force from Thommond. In 1171, King Henry II of England landed in nearby Waterford Harbour with one of the largest injections of English military strength into Ireland. On the banks of the Suir, Henry secured the submission of many of the kings and chiefs of southern Ireland; including Tuaisceart Osraige's king, Domnall Mac Giolla Phádraig.[21] In 1172, the Norman adventurer Adam de Hereford was granted land by Strongbow in Aghaboe, north Osraige.[22] After Henry was recalled from Ireland to deal with the aftermath of Thomas Becket's murder and the Revolt of 1173–74, Ossory continued to be a theatre of conflict. Raymond FitzGerald plundered Offaly and travelled through that land to win a naval engagement at Waterford. Later, a force from Dublin inflicted a defeat on Hervey de Clare in Ossory. In 1175, the prince of Ossory assisted a force under Raymond FitzGerald to relieve the city of Limerick which had been besieged by the forces of Domnall Mór Ua Briain. Later, Gerald of Wales relates a defeat of the men of Kilkenny and their prince by a Norman force from Meath. The noted adventurer Robert le Poer won lands in Ossory, but was later killed there against the natives. In 1185, Prince John, then Lord of Ireland and future King of England, travelled from England to Ireland to consolidate the possession of Ireland, landing at Waterford near the border of Ossory. He secured the allegiance of the Irish princes and travelled through Ossory to Dublin, ordering several castles to be constructed in the region.

The last recorded king of central Osraige was Maelseachaill Mac Gilla Patráic, who died in either 1193 or 1194.[23][24] However, the kingdom and a continuous succession of rulers remained intact in the north, subsequently called "Upper Ossory" into the mid-sixteenth century.

Outside links

- History of Ossory papers at Academia.edu

- The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland (English trans.) at CELT

- The Annals of Ulster (English trans.) at CELT

- The Annals of Loch Cé (English trans.) at CELT

- Genealogies from Rawlinson B502 at CELT

- Doctoral thesis by Mark Zumbuhl which examines Osraige's kingship in the Central Middle Ages

- Osraige History on The Fitzpatrick - Mac Giolla Phádraig Clan Society

- Contents of Bodleian Library MS Rawl. B. 502; Early Manuscripts at Oxford University

- Irish Geography; Volume 41, Issue 1, 2008

- Irish History in Maps, "The Osraighe Region"

- Baldwin, Stewart. Kings of Osraige (Ossory)

- OLL (Ossory, Laois, and Leinster)

- St. Canice's Cathedral and Round Tower, Kilkenny

- Osraige.com family history site

- Fitzpatrick - Mac Giolla Phádraig Clan Society

References

- ↑ "Osraige pronunciation: How to pronounce Osraige in Irish". 2014-11-19. http://forvo.com/word/osraige/.

- ↑ Collectanea de rebus hibernicis. 1790. pp. 331–. https://books.google.com/books?id=OAA-AAAAcAAJ&pg=PA331.

- ↑ Byrne, Irish kings and high-kings, maps on pp. 133 & 172–173; Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, p. 236, map 9 & p. 532, map 13.

- ↑ Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (1907). The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. The Society. p. 26. https://books.google.com/books?id=JE8OAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA26. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ↑ Genealogies from Rawlinson B 502, at CELT, pg 15–16

- ↑ "Cσir Anmann: Fitness of Names". http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/fitness_of_names.html.

- ↑ Byrne, p. 201

- ↑ Ó Néill, 'Osraige'; Doherty, 'Érainn'

- ↑ Byrne, p. 163

- ↑ Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland, p. 541

- ↑ Ptolemy's map of Ireland: a modern decoding. R. Darcy, William Flynn. Irish Geography Vol. 41, Iss. 1, 2008. Figure 1.

- ↑ U1103.5

- ↑ M1154.15

- ↑ M1156.17

- ↑ M1157.10

- ↑ MCB1167.4

- ↑ MCB1167.6

- ↑ MCB1167.9

- ↑ MCB1169.2

- ↑ Lyng. The Fitzpatricks of Ossory, p. 260.

- ↑ MCB1172.2

- ↑ Public Record Office, Ireland (1879). National Manuscripts of Ireland: Account of Facsimiles of National ... - Ireland. Public Record Office. p. 1. https://books.google.com/books?id=5KTPAAAAMAAJ&q=sir+john+gilbert+facsimiles+of+national+manuscripts&pg=PA1. Retrieved 2017-03-16.

- ↑ LC1193.13

- ↑ FM1194.6

Bibliography

- Francis John Byrne (1987), Irish Kings and High-Kings, London: Batsford, ISBN 978-0-7134-5882-4

- Carrigan, William. The History and Antiquities of the Diocese of Ossory. (Vols. I-V) Dublin: Sealy, Bryers & Walker, 1905. Print.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2000), Early Christian Ireland, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-36395-2

- Doherty, Charles., 'Érainn', in Seán Duffy (ed.), Mediæval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. 2005. p. 156.

- Downham, Clare (2004), "The career of Cearbhall of Osraige", Ossory, Laois and Leinster 1: 1–18, SSN 1649-4938

- Edwards, David. "Collaboration without Anglicization: The Macgiollapadraig Lordship and Tudor Reform." Gaelic Ireland c. 1250 – c. 1650: Land, Lordship, & Settlement. Ed. Patrick J. Duffy, David Edwards, & Elizabeth FitzPatrick. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2001. pgs. 77–97. Print.

- Hariman, James. Irish Minstrelsy or Bardic Remains of Ireland; with English Poetical Translations. Vol. II. London: Joseph Robins, Bride Court, Bridge Street, 1831.

- Lyng, T., The FitzPatricks of Ossory, Old Kilkenny Review, Vol. 2, no. 3, 1981.

- Mac Niocaill, Gearóid (1972), Ireland before the Vikings, The Gill History of Ireland, 1, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-7171-0558-8

- Morris, Henry The Ancient Kingdom of Ossory, The Irish Monthly, Vol. 50, No. 588 (Jun., 1922), pp. 230–236. Published by: Irish Jesuit Province (JSTOR Article Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20505867)

- Ó Drisceoil, Cóilín. "Probing the past: a geophysical survey at St. Canice's Cathedral, Kilkenny." Old Kilkenny Review No. 58 (2004) p. 80–106. Print.

- Ó Néill, Pádraig. "Osraige", in Seán Duffy (ed.), Mediæval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. 2005. p. 358

- Radner, Joan. Writing History: Early Irish Historiography and the Significance of Form, in 'Celtica 23' (1999); p. 312–325